Costa Rican Household Poverty Level Prediction

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Data Wrangling

- 3. Exploratory Data Analysis

- 4. Feature Engineering

- 5. Exploring Household Variables

- 6. Machine Learning Modeling

1. Introduction

The Inter-American Development Bank is asking the Kaggle community for help with income qualification for some of the world’s poorest families.

Here’s the backstory: Many social programs have a hard time making sure the right people are given enough aid. It’s especially tricky when a program focuses on the poorest segment of the population. The world’s poorest typically can’t provide the necessary income and expense records to prove that they qualify.

In Latin America, one popular method uses an algorithm to verify income qualification. It’s called the Proxy Means Test (or PMT). With PMT, agencies use a model that considers a family’s observable household attributes like the material of their walls and ceiling, or the assets found in the home to classify them and predict their level of need.

While this is an improvement, accuracy remains a problem as the region’s population grows and poverty declines. Beyond Costa Rica, many countries face this same problem of inaccurately assessing social need.

Problem and Data Explanation

The data for this competition is provided in two files: train.csv and test.csv. The training set has 9557 rows and 143 columns while the testing set has 23856 rows and 142 columns. Each row represents one individual and each column is a feature, either unique to the individual, or for the household of the individual. The training set has one additional column, Target, which represents the poverty level on a 1-4 scale and is the label for the competition. A value of 1 is the most extreme poverty.

This is a supervised multi-class classification machine learning problem:

- Supervised: provided with the labels for the training data

- Multi-class classification: Labels are discrete values with 4 classes

Objective

The objective is to predict poverty on a household level. We are given data on the individual level with each individual having unique features but also information about their household. In order to create a dataset for the task, we’ll have to perform some aggregations of the individual data for each household. Moreover, we have to make a prediction for every individual in the test set, but “ONLY the heads of household are used in scoring” which means we want to predict poverty on a household basis.

The Target values represent poverty levels as follows:

1 = extreme poverty 2 = moderate poverty 3 = vulnerable households 4 = non vulnerable households

The explanations for all 143 columns can be found in the competition documentation , but a few to note are below:

- Id : a unique identifier for each individual, this should not be a feature that we use!

- idhogar : a unique identifier for each household. This variable is not a feature, but will be used to group individuals by - household as all individuals in a household will have the same identifier.

- parentesco1 : indicates if this person is the head of the household.

- Target : the label, which should be equal for all members in a household

When we make a model, we’ll train on a household basis with the label for each household the poverty level of the head of household. The raw data contains a mix of both household and individual characteristics and for the individual data, we will have to find a way to aggregate this for each household. Some of the individuals belong to a household with no head of household which means that unfortunately we can’t use this data for training. These issues with the data are completely typical of real-world data and hence this problem is great preparation for the datasets you’ll encounter in a data science job!

# Import modules

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Visualization

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Set a few plotting defaults

%matplotlib inline

plt.style.use('fivethirtyeight')

plt.rcParams['font.size'] = 18

plt.rcParams['patch.edgecolor'] = 'k'

# Ignore Warning

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore', category = RuntimeWarning)

# Read the data

train = pd.read_csv("train.csv")

test = pd.read_csv("test.csv")

2. Data Wrangling

# Shape of train and test data

print("Train:",train.shape)

print("Test:",test.shape)

Train: (9557, 143)

Test: (23856, 142)

# Let's see some informationof train and test data

train.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 9557 entries, 0 to 9556

Columns: 143 entries, Id to Target

dtypes: float64(8), int64(130), object(5)

memory usage: 10.4+ MB

test.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 23856 entries, 0 to 23855

Columns: 142 entries, Id to agesq

dtypes: float64(8), int64(129), object(5)

memory usage: 25.8+ MB

This tells us there are 130 integer columns, 8 float (numeric) columns, and 5 object columns. The integer columns probably represent Boolean variables (that take on either 0 or 1) or ordinal variables with discrete ordered values. The object columns might pose an issue because they cannot be fed directly into a machine learning model.

The test data which has many more rows (individuals) than the train. It does have one fewer column because there’s no Target!

### Null and missing values

# Check for Null values

train.isnull().sum()

Id 0

v2a1 6860

hacdor 0

rooms 0

hacapo 0

v14a 0

refrig 0

v18q 0

v18q1 7342

r4h1 0

r4h2 0

r4h3 0

r4m1 0

r4m2 0

r4m3 0

r4t1 0

r4t2 0

r4t3 0

tamhog 0

tamviv 0

escolari 0

rez_esc 7928

hhsize 0

paredblolad 0

paredzocalo 0

paredpreb 0

pareddes 0

paredmad 0

paredzinc 0

paredfibras 0

...

bedrooms 0

overcrowding 0

tipovivi1 0

tipovivi2 0

tipovivi3 0

tipovivi4 0

tipovivi5 0

computer 0

television 0

mobilephone 0

qmobilephone 0

lugar1 0

lugar2 0

lugar3 0

lugar4 0

lugar5 0

lugar6 0

area1 0

area2 0

age 0

SQBescolari 0

SQBage 0

SQBhogar_total 0

SQBedjefe 0

SQBhogar_nin 0

SQBovercrowding 0

SQBdependency 0

SQBmeaned 5

agesq 0

Target 0

Length: 143, dtype: int64

Number of tablets household owns(v18q1) , Monthly rent payment(v2a1), Years behind in school(rez_esc) have most missing values.

3. Exploratory Data Analysis

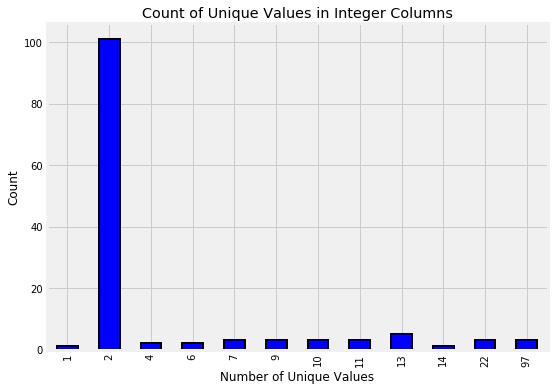

Integer Columns

Let’s look at the distribution of unique values in the integer columns. For each column, we’ll count the number of unique values and show the result in a bar plot.

train.select_dtypes(np.int64).nunique().value_counts().sort_index().plot.bar(color = 'blue',

figsize = (8, 6),

edgecolor = 'k', linewidth = 2);

plt.xlabel('Number of Unique Values'); plt.ylabel('Count');

plt.title('Count of Unique Values in Integer Columns');

The columns with only 2 unique values represent Booleans (0 or 1). In a lot of cases, this boolean information is already on a household level. For example, the refrig column says whether or not the household has a refrigerator. When it comes time to make features from the Boolean columns that are on the household level, we will not need to aggregate these. However, the Boolean columns that are on the individual level will need to be aggregated.

3.2 Float Columns

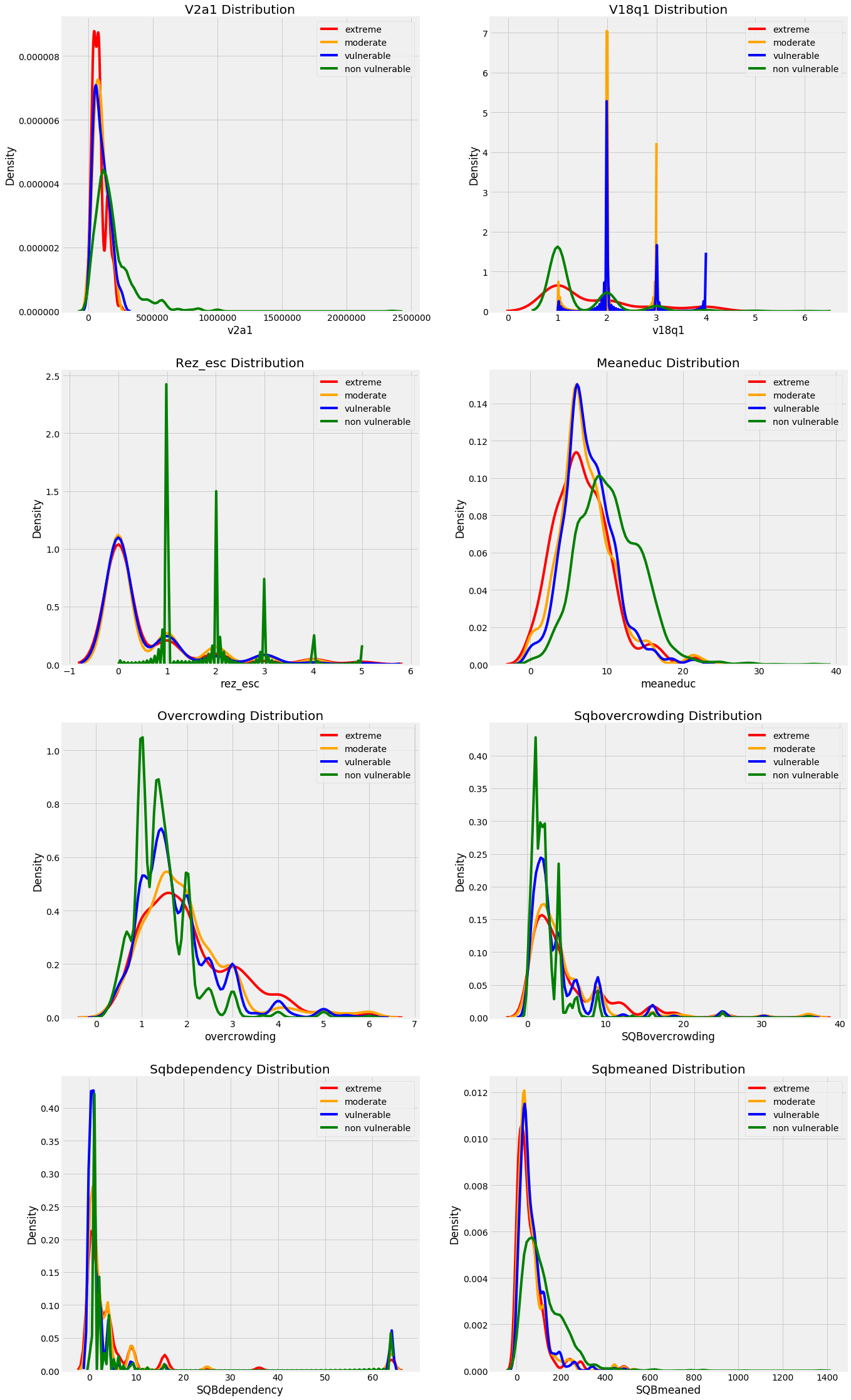

Another column type is floats which represent continuous variables. We can make a quick distribution plot to show the distribution of all float columns. We’ll use an OrderedDict to map the poverty levels to colors because this keeps the keys and values in the same order as we specify (unlike a regular Python dictionary).

The following graphs shows the distributions of the float columns colored by the value of the Target. With these plots, we can see if there is a significant difference in the variable distribution depending on the household poverty level.

from collections import OrderedDict

plt.figure(figsize = (20, 16))

plt.style.use('fivethirtyeight')

# Color mapping

colors = OrderedDict({1: 'red', 2: 'orange', 3: 'blue', 4: 'green'})

poverty_mapping = OrderedDict({1: 'extreme', 2: 'moderate', 3: 'vulnerable', 4: 'non vulnerable'})

# Iterate through the float columns

for i, col in enumerate(train.select_dtypes('float')):

ax = plt.subplot(4, 2, i + 1)

# Iterate through the poverty levels

for poverty_level, color in colors.items():

# Plot each poverty level as a separate line

sns.kdeplot(train.loc[train['Target'] == poverty_level, col].dropna(),

ax = ax, color = color, label = poverty_mapping[poverty_level])

plt.title(f'{col.capitalize()} Distribution'); plt.xlabel(f'{col}'); plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.subplots_adjust(top = 2)

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

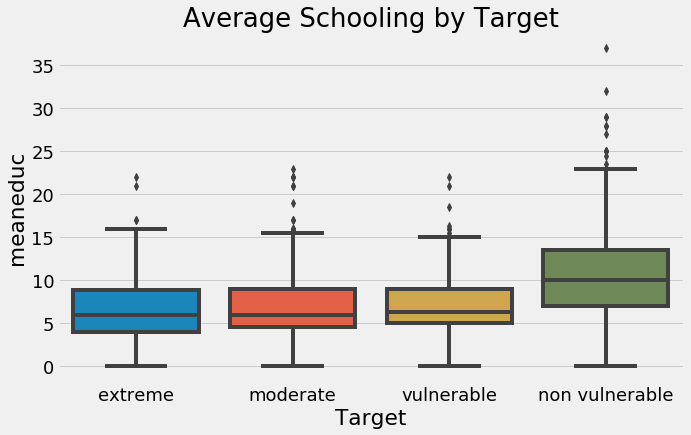

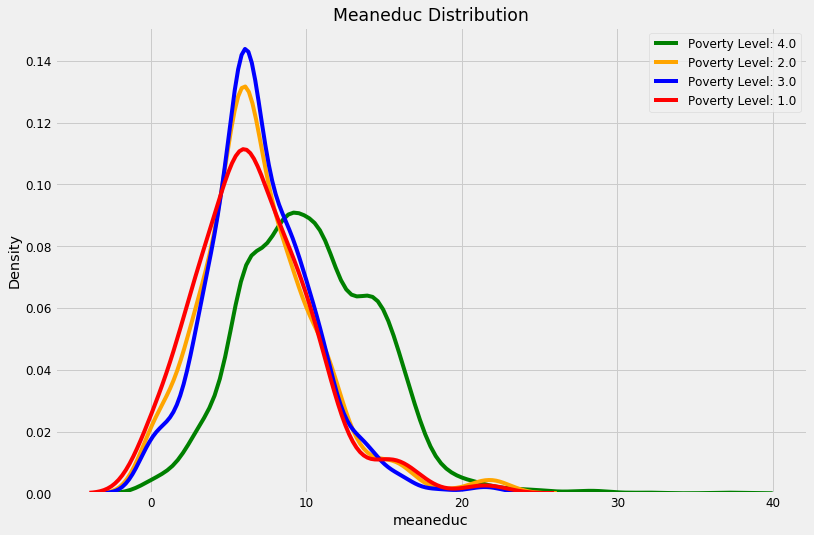

These plots give us a sense of which variables may be most “relevant” to a model. For example, the meaneduc, representing the average education of the adults in the household appears to be related to the poverty level: a higher average adult education leads to higher values of the target which are less severe levels of poverty. The theme of the importance of education is one we will come back to again and again in this notebook!

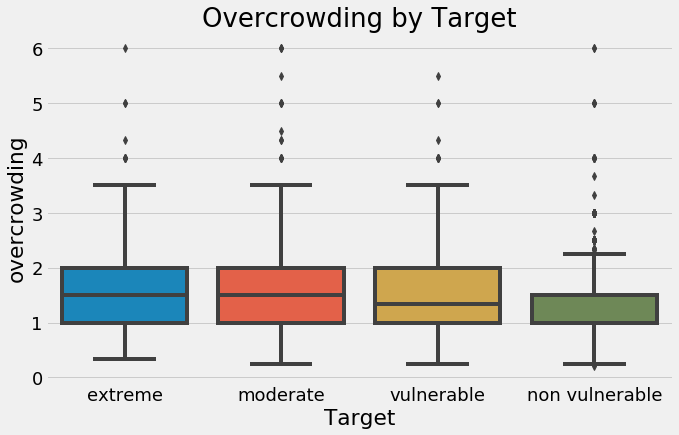

- We can see that non vulnarable have more numbers of years of education.

- We can see that there are less number of people living in one room in the non vulnarable catogery and it increases as the poverty increases.

Object Columns

train.select_dtypes('object').head()

| Id | idhogar | dependency | edjefe | edjefa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ID_279628684 | 21eb7fcc1 | no | 10 | no |

| 1 | ID_f29eb3ddd | 0e5d7a658 | 8 | 12 | no |

| 2 | ID_68de51c94 | 2c7317ea8 | 8 | no | 11 |

| 3 | ID_d671db89c | 2b58d945f | yes | 11 | no |

| 4 | ID_d56d6f5f5 | 2b58d945f | yes | 11 | no |

The Id and idhogar object types make sense because these are identifying variables. However, the other columns seem to be a mix of strings and numbers which we’ll need to address before doing any machine learning. According to the documentation for these columns:

- dependency: Dependency rate, calculated = (number of members of the household younger than 19 or older than 64)/(number of member of household between 19 and 64)

- edjefe: years of education of male head of household, based on the interaction of escolari (years of education), head of household and gender, yes=1 and no=0

- edjefa: years of education of female head of household, based on the interaction of escolari (years of education), head of household and gender, yes=1 and no=0 These explanations clear up the issue. For these three variables, “yes” = 1 and “no” = 0. We can correct the variables using a mapping and convert to floats.

mapping = {"yes": 1, "no": 0}

# Apply same operation to both train and test

for df in [train, test]:

# Fill in the values with the correct mapping

df['dependency'] = df['dependency'].replace(mapping).astype(np.float64)

df['edjefa'] = df['edjefa'].replace(mapping).astype(np.float64)

df['edjefe'] = df['edjefe'].replace(mapping).astype(np.float64)

train[['dependency', 'edjefa', 'edjefe']].describe()

| dependency | edjefa | edjefe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| count | 9557.000000 | 9557.000000 | 9557.000000 |

| mean | 1.149550 | 2.896830 | 5.096788 |

| std | 1.605993 | 4.612056 | 5.246513 |

| min | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| 25% | 0.333333 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| 50% | 0.666667 | 0.000000 | 6.000000 |

| 75% | 1.333333 | 6.000000 | 9.000000 |

| max | 8.000000 | 21.000000 | 21.000000 |

plt.figure(figsize = (16, 12))

# Iterate through the float columns

for i, col in enumerate(['dependency', 'edjefa', 'edjefe']):

ax = plt.subplot(3, 1, i + 1)

# Iterate through the poverty levels

for poverty_level, color in colors.items():

# Plot each poverty level as a separate line

sns.kdeplot(train.loc[train['Target'] == poverty_level, col].dropna(),

ax = ax, color = color, label = poverty_mapping[poverty_level])

plt.title(f'{col.capitalize()} Distribution'); plt.xlabel(f'{col}'); plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.subplots_adjust(top = 2)

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

From the plots we can see that

- Years of education of male and female head of household is very low in extreme poverty and high in non-vulnerable.

- Dependency is very low in non vulnareable.

Join Train and Test Set

We’ll join together the training and testing dataframes. This is important once we start feature engineering because we want to apply the same operations to both dataframes so we end up with the same features. Later we can separate out the sets based on the Target.

# Add null Target column to test

test['Target'] = np.nan

train_len = len(train)

data = pd.concat(objs=[train, test], axis=0).reset_index(drop=True)

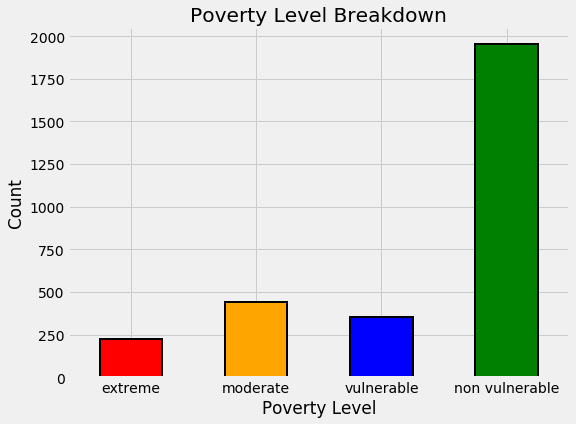

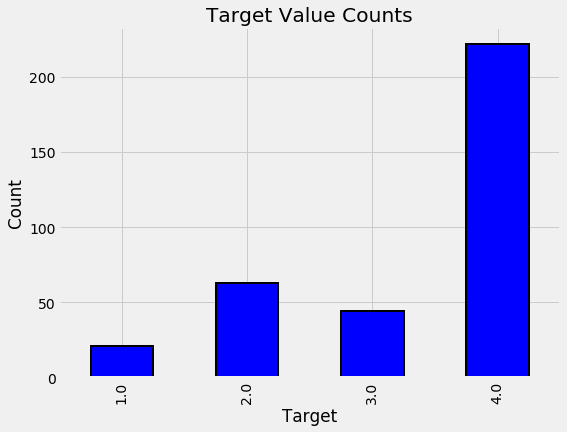

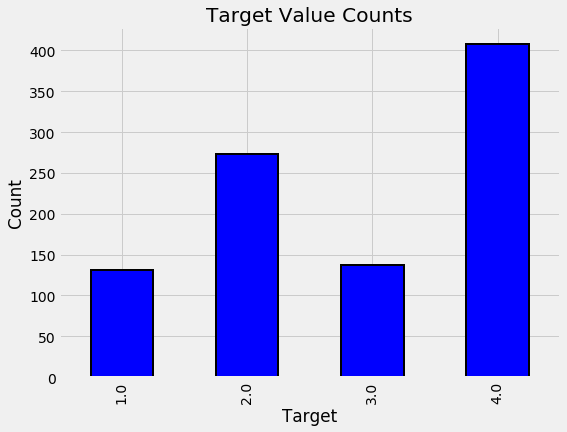

Exploring Label Distribution

Next, we can get an idea of how imbalanced the problem is by looking at the distribution of labels. There are four possible integer levels, indicating four different levels of poverty. To look at the correct labels, we’ll subset only to the columns where parentesco1 == 1 because this is the head of household, the correct label for each household.

The bar plot below shows the distribution of training labels (since there are no testing labels).

# Heads of household

heads = data.loc[data['parentesco1'] == 1].copy()

# Labels for training

train_labels = data.loc[(data['Target'].notnull()) & (data['parentesco1'] == 1), ['Target', 'idhogar']]

# Value counts of target

label_counts = train_labels['Target'].value_counts().sort_index()

# Bar plot of occurrences of each label

label_counts.plot.bar(figsize = (8, 6),

color = colors.values(),

edgecolor = 'k', linewidth = 2)

# labels and titles

plt.xlabel('Poverty Level'); plt.ylabel('Count');

plt.xticks([x - 1 for x in poverty_mapping.keys()],

list(poverty_mapping.values()), rotation = 360)

plt.title('Poverty Level Breakdown');

label_counts

1.0 222

2.0 442

3.0 355

4.0 1954

Name: Target, dtype: int64

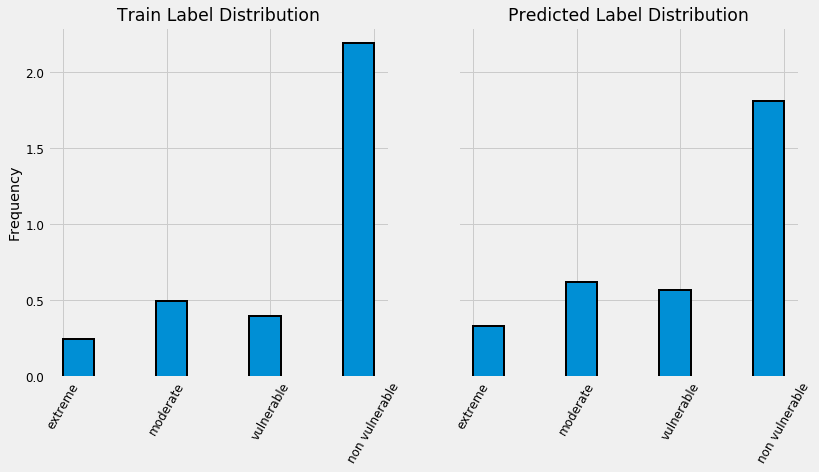

By this plot you and I can see that we are dealing with an imbalanced class problem. There are many more households that classify as non vulnerable than in any other category. The extreme poverty class is the smallest.

One of the major problem with imbalanced classification problems is that the machine learning model will have a difficult time predicting the minority classes because it will get far less examples.

Wrong Labels

For this problem, some of the labels are not correct because individuals in the same household have a different poverty level. We are told to use the head of household as the true label that information makes our job much easier. We will fix the issue with the labels.

Identify Errors

To find the households with different labels for family members, we can group the data by the household and then check if there is only one unique value of the Target.

# Groupby the household and figure out the number of unique values

all_equal = train.groupby('idhogar')['Target'].apply(lambda x: x.nunique() == 1)

# Households where targets are not all equal

not_equal = all_equal[all_equal != True]

print('There are {} households where the family members do not all have the same target.'.format(len(not_equal)))

There are 85 households where the family members do not all have the same target.

# Example

train[train['idhogar'] == not_equal.index[0]][['idhogar', 'parentesco1', 'Target']]

| idhogar | parentesco1 | Target | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7651 | 0172ab1d9 | 0 | 3 |

| 7652 | 0172ab1d9 | 0 | 2 |

| 7653 | 0172ab1d9 | 0 | 3 |

| 7654 | 0172ab1d9 | 1 | 3 |

| 7655 | 0172ab1d9 | 0 | 2 |

The correct label for the head of household is where parentesco1 == 1. For this household, the correct label is 3 for all members. We will correct this by reassigning all the individuals in this household the correct poverty level.

Families without Heads of Household

We will correct all the label discrepancies by assigning the individuals in the same household the label of the head of household. Let’s check if there are households without a head of household and if the members of those households have differing values of the label.

households_leader = train.groupby('idhogar')['parentesco1'].sum()

# Find households without a head

households_no_head = train.loc[train['idhogar'].isin(households_leader[households_leader == 0].index), :]

print('There are {} households without a head.'.format(households_no_head['idhogar'].nunique()))

There are 15 households without a head.

# Find households without a head and where labels are different

households_no_head_equal = households_no_head.groupby('idhogar')['Target'].apply(lambda x: x.nunique() == 1)

print('{} Households with no head have different labels.'.format(sum(households_no_head_equal == False)))

0 Households with no head have different labels.

Labels

Let’s correct the labels for the households that have a Head and the members have different poverty levels.

# Iterate through each household

for household in not_equal.index:

# Find correct label for head of household

true_target = int(train[(train['idhogar'] == household) & (train['parentesco1'] == 1.0)]['Target'])

# Set correct label for all members in the household

train.loc[train['idhogar'] == household, 'Target'] = true_target

# Groupby the household and figure out the number of unique values

all_equal = train.groupby('idhogar')['Target'].apply(lambda x: x.nunique() == 1)

# Households where targets are not all equal

not_equal = all_equal[all_equal != True]

print('There are {} households where the family members do not have the same target.'.format(len(not_equal)))

There are 0 households where the family members do not have the same target.

Missing Data

First we can look at the percentage of missing values in each column.

# Number of missing in each column

missing = pd.DataFrame(data.isnull().sum()).rename(columns = {0: 'total'})

# Percentage missing

missing['percent'] = missing['total'] / len(data)

missing.sort_values('percent', ascending = False).head(10).drop('Target')

| total | percent | |

|---|---|---|

| rez_esc | 27581 | 0.825457 |

| v18q1 | 25468 | 0.762218 |

| v2a1 | 24263 | 0.726154 |

| SQBmeaned | 36 | 0.001077 |

| meaneduc | 36 | 0.001077 |

| hogar_adul | 0 | 0.000000 |

| parentesco10 | 0 | 0.000000 |

| parentesco11 | 0 | 0.000000 |

| parentesco12 | 0 | 0.000000 |

In Target we put NaN in the test data. So, there are 3 columns with a high percentage of missing values.

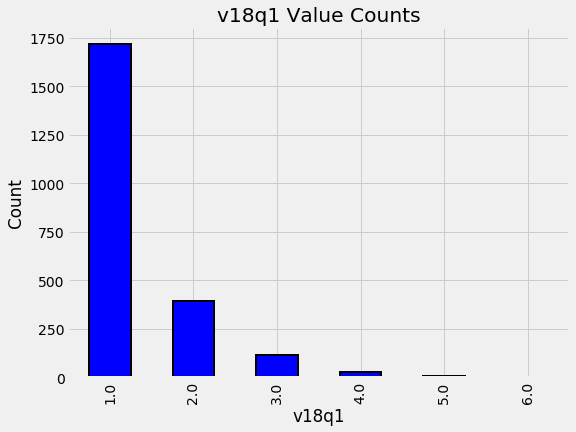

v18q1: Number of tablets

Let’s start with v18q1 which indicates the number of tablets owned by a family. We can look at the value counts of this variable. Since this is a household variable, it only makes sense to look at it on a household level, so we’ll only select the rows for the head of household.

Function to Plot Value Counts¶

Since we might want to plot value counts for different columns, we can write a simple function that will do it for us!

def plot_value_counts(df, col, heads_only = False): “"”Plot value counts of a column, optionally with only the heads of a household””” # Select heads of household if heads_only: df = df.loc[df[‘parentesco1’] == 1].copy()

plt.figure(figsize = (8, 6))

df[col].value_counts().sort_index().plot.bar(color = 'blue',

edgecolor = 'k',

linewidth = 2)

plt.xlabel(f'{col}'); plt.title(f'{col} Value Counts'); plt.ylabel('Count')

plt.show();

# Import function to plot value counts of column

from costarican.data_plot import plot_value_counts

# Plot the data

plot_value_counts(heads, 'v18q1')

By looking into the data we can see that the most common number of tablets to own is 1. However, We also need to think about the data that is missing. In this case, it could be that families with a NaN in this category just do not own a tablet! If we look at the data definitions, we can see that v18q indicates whether or not a family owns a tablet. We will investigate this column combined with the number of tablets to see if the hypothesis holds true.

We can groupby the value of v18q (which is 1 for owns a tablet and 0 for does not) and then calculate the number of null values for v18q1. This will tell us if the null values represent that the family does not own a tablet.

heads.groupby('v18q')['v18q1'].apply(lambda x: x.isnull().sum())

v18q

0 8044

1 0

Name: v18q1, dtype: int64

So, Every family that has NaN for v18q1 does not own a tablet. So, we will fill in this missing value with zero.

data['v18q1'] = data['v18q1'].fillna(0)

v2a1: Monthly rent payment

The next missing column is v2a1 which represents the montly rent payment.

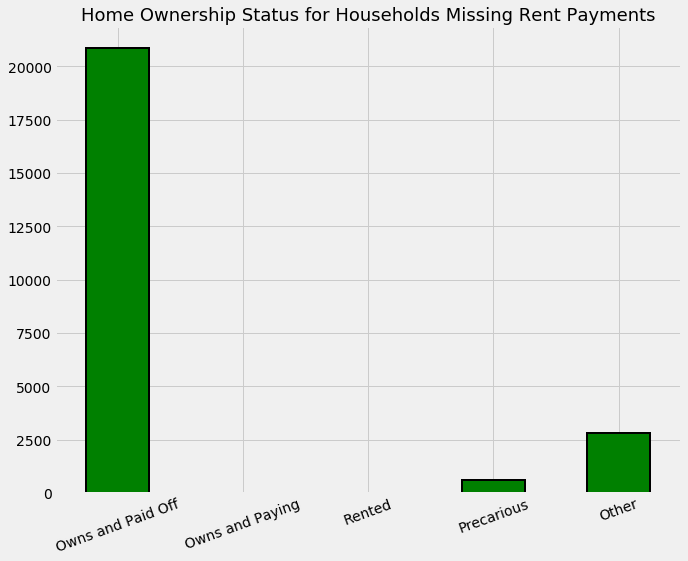

In addition to looking at the missing values of the monthly rent payment, it will be interesting to also look at the distribution of tipovivi_, the columns showing the ownership/renting status of the home. For this plot, we will show the ownership status of those homes with a NaN for the monthyl rent payment.

# Variables indicating home ownership

own_variables = [x for x in data if x.startswith('tipo')]

# Plot of the home ownership variables for home missing rent payments

data.loc[data['v2a1'].isnull(), own_variables].sum().plot.bar(figsize = (10, 8),

color = 'green',

edgecolor = 'k', linewidth = 2);

plt.xticks([0, 1, 2, 3, 4],

['Owns and Paid Off', 'Owns and Paying', 'Rented', 'Precarious', 'Other'],

rotation = 20)

plt.title('Home Ownership Status for Households Missing Rent Payments', size = 18);

The meaning of the home ownership variables:

- tipovivi1, =1 own and fully paid house

- tipovivi2, “=1 own, paying in installments”

- tipovivi3, =1 rented

- tipovivi4, =1 precarious

- tipovivi5, “=1 other(assigned, borrowed)”

Mostly the households that do not have a monthly rent payment generally own their own home. In some other situations, we are not sure of the reason for the missing information.

For the houses that are owned and have a missing monthly rent payment, we will set the value of the rent payment to zero and for the other homes, we will leave the missing values to be imputed but we’ll add a flag (Boolean) column indicating that these households had missing values.

# Fill in households that own the house with 0 rent payment

data.loc[(data['tipovivi1'] == 1), 'v2a1'] = 0

# Create missing rent payment column

data['v2a1-missing'] = data['v2a1'].isnull()

data['v2a1-missing'].value_counts()

False 29994

True 3419

Name: v2a1-missing, dtype: int64

rez_esc: years behind in school

The last column with a high percentage of missing values is rez_esc indicating years behind in school. For the families with a null value, it is possible that they have no children currently in school. Let’s test this out by finding the ages of those who have a missing value in this column and the ages of those who do not have a missing value.

data.loc[data['rez_esc'].notnull()]['age'].describe()

count 5832.000000

mean 12.185700

std 3.198618

min 7.000000

25% 9.000000

50% 12.000000

75% 15.000000

max 17.000000

Name: age, dtype: float64

Now we can see that the oldest age with a missing value is 17. For anyone older than this, maybe we can assume that they are simply not in school. Let’s look at the ages of those who have a missing value.

data.loc[data['rez_esc'].isnull()]['age'].describe()

count 27581.000000

mean 39.110656

std 20.983114

min 0.000000

25% 24.000000

50% 38.000000

75% 54.000000

max 97.000000

Name: age, dtype: float64

Anyone younger or older than 7-19 presumably has no years behind and therefore the value should be set to 0. For this variable, if the individual is over 19 and they have a missing value, or if they are younger than 7 and have a missing value we can set it to zero. For anyone else, we’ll leave the value to be imputed and add a boolean flag.

# If individual is over 19 or younger than 7 and missing years behind, set it to 0

data.loc[((data['age'] > 19) | (data['age'] < 7)) & (data['rez_esc'].isnull()), 'rez_esc'] = 0

# Add a flag for those between 7 and 19 with a missing value

data['rez_esc-missing'] = data['rez_esc'].isnull()

There is also one outlier in the rez_esc column. In the competition discussions, I learned that the maximum value for this variable is 5. Therefore, any values above 5 should be set to 5.

data.loc[data['rez_esc'] > 5, 'rez_esc'] = 5

Plot Two Categorical Variables

# Import function to plot

from costarican.cat_plot import categorical_plot

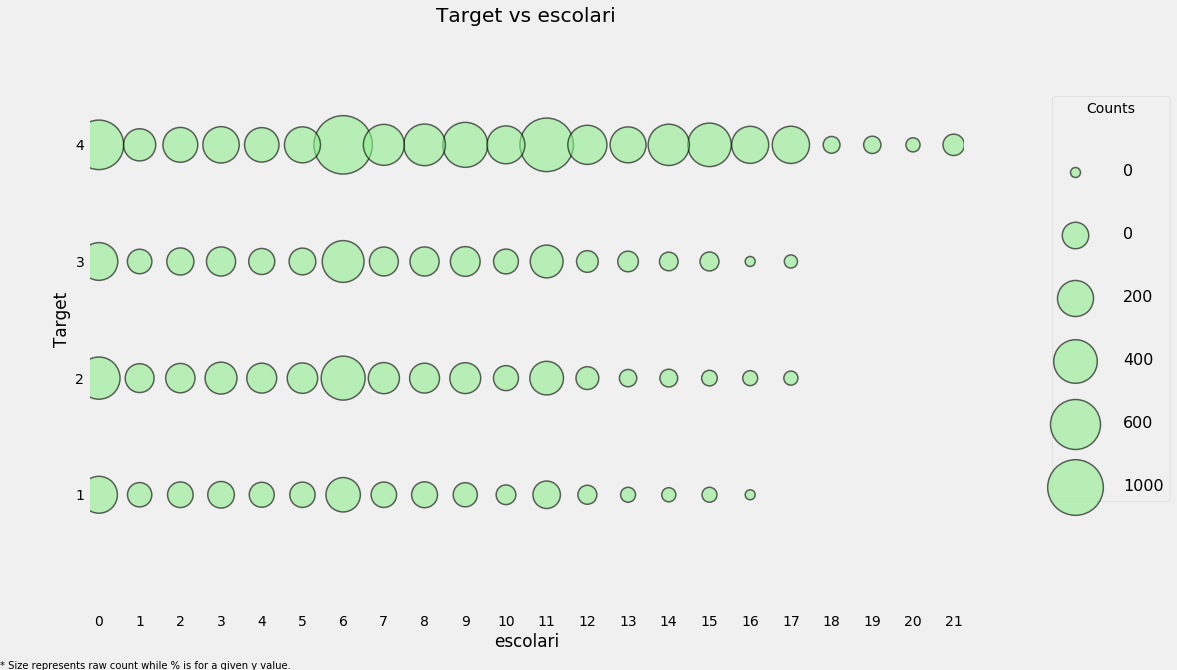

categorical_plot('rez_esc', 'Target', data);

The size of the markers represents the raw count. To read the plot, choose a given y-value and then read across the row. For example, with a poverty level of 1, 93% of individuals have no years behind with a total count of around 800 individuals and about 0.4% of individuals are 5 years behind with about 50 total individuals in this category. This plot attempts to show both the overall counts and the within category proportion.

# Poverty vs years of schooling

categorical_plot('escolari', 'Target', data, annotate = False)

We will fill in the remaining missing values in each column. As a final step with the missing values, we can plot the distribution of target for the case where either of these values are missing.

plot_value_counts(data[(data['rez_esc-missing'] == 1)],

'Target')

The distribution here seems to match that for all the data at large.

plot_value_counts(data[(data['v2a1-missing'] == 1)],

'Target')

This looks like it could be an indicator of more poverty given the higher prevalence of 2: moderate poverty.

Feature Engineering

Column Definitions

We will define different variables because we need to treat some of them in a different manner. Once we have the variables defined on each level, we can work to start aggregating them as needed.

The process is as follows

- Break variables into household level and invididual level

- Find suitable aggregations for the individual level data

- Ordinal variables can use statistical aggregations

- Boolean variables can also be aggregated but with fewer stats

- Join the individual aggregations to the household level data

Define Variable Categories

There are several different categories of variables:

- Individual Variables: these are characteristics of each individual rather than the household

- Boolean: Yes or No (0 or 1)

- Ordered Discrete: Integers with an ordering

- Household variables

- Boolean: Yes or No

- Ordered Discrete: Integers with an ordering

- Continuous numeric

- Squared Variables: derived from squaring variables in the data

- Id variables: identifies the data and should not be used as features

First we manually define the variables in each category.

#These will be kept as is in the data since we need them for identification.

id_ = ['Id', 'idhogar', 'Target']

# Individual boolean

ind_bool = ['v18q', 'dis', 'male', 'female', 'estadocivil1', 'estadocivil2', 'estadocivil3',

'estadocivil4', 'estadocivil5', 'estadocivil6', 'estadocivil7',

'parentesco1', 'parentesco2', 'parentesco3', 'parentesco4', 'parentesco5',

'parentesco6', 'parentesco7', 'parentesco8', 'parentesco9', 'parentesco10',

'parentesco11', 'parentesco12', 'instlevel1', 'instlevel2', 'instlevel3',

'instlevel4', 'instlevel5', 'instlevel6', 'instlevel7', 'instlevel8',

'instlevel9', 'mobilephone', 'rez_esc-missing']

# Individual Numbers

ind_ordered = ['rez_esc', 'escolari', 'age']

# Household boolean

hh_bool = ['hacdor', 'hacapo', 'v14a', 'refrig', 'paredblolad', 'paredzocalo',

'paredpreb','pisocemento', 'pareddes', 'paredmad',

'paredzinc', 'paredfibras', 'paredother', 'pisomoscer', 'pisoother',

'pisonatur', 'pisonotiene', 'pisomadera',

'techozinc', 'techoentrepiso', 'techocane', 'techootro', 'cielorazo',

'abastaguadentro', 'abastaguafuera', 'abastaguano',

'public', 'planpri', 'noelec', 'coopele', 'sanitario1',

'sanitario2', 'sanitario3', 'sanitario5', 'sanitario6',

'energcocinar1', 'energcocinar2', 'energcocinar3', 'energcocinar4',

'elimbasu1', 'elimbasu2', 'elimbasu3', 'elimbasu4',

'elimbasu5', 'elimbasu6', 'epared1', 'epared2', 'epared3',

'etecho1', 'etecho2', 'etecho3', 'eviv1', 'eviv2', 'eviv3',

'tipovivi1', 'tipovivi2', 'tipovivi3', 'tipovivi4', 'tipovivi5',

'computer', 'television', 'lugar1', 'lugar2', 'lugar3',

'lugar4', 'lugar5', 'lugar6', 'area1', 'area2', 'v2a1-missing']

# Household numbers

hh_ordered = [ 'rooms', 'r4h1', 'r4h2', 'r4h3', 'r4m1','r4m2','r4m3', 'r4t1', 'r4t2',

'r4t3', 'v18q1', 'tamhog','tamviv','hhsize','hogar_nin',

'hogar_adul','hogar_mayor','hogar_total', 'bedrooms', 'qmobilephone']

# Household continuous numbers

hh_cont = ['v2a1', 'dependency', 'edjefe', 'edjefa', 'meaneduc', 'overcrowding']

# Squared Variables

sqr_ = ['SQBescolari', 'SQBage', 'SQBhogar_total', 'SQBedjefe',

'SQBhogar_nin', 'SQBovercrowding', 'SQBdependency', 'SQBmeaned', 'agesq']

# To check no repitition

x = ind_bool + ind_ordered + id_ + hh_bool + hh_ordered + hh_cont + sqr_

from collections import Counter

print('No repeats: ', np.all(np.array(list(Counter(x).values())) == 1))

print('Covered every variable: ', len(x) == data.shape[1])

No repeats: True

Covered every variable: True

Squared Variables

Let’s remove all of the squared variables to help linear models learn relationships that are non-linear. However, since we will be using more complex models, these squared features are redundant and are highly correlated with the non-squared version, and hence will hurt our model by adding irrelevant information and also slowing down training.

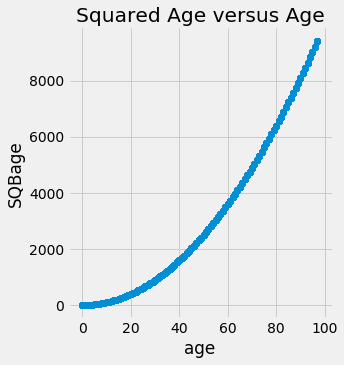

sns.lmplot('age', 'SQBage', data = data, fit_reg=False);

plt.title('Squared Age versus Age');

Highly correlated, and we don’t need to keep both in our data. Therefore let’s remove it.

# Remove squared variables

data = data.drop(columns = sqr_)

data.shape

(33413, 136)

Household Level Variables

First let’s subset to the heads of household and then to the household level variables.

heads = data.loc[data['parentesco1'] == 1, :]

heads = heads[id_ + hh_bool + hh_cont + hh_ordered]

heads.shape

(10307, 99)

For most of the household level variables, we can simply keep them as it is. Since we want to make predictions for each household, we will use these variables as features. However, we can also remove some redundant variables and also add in some more features derived from existing data.

Redundant Household Variables

Let’s take a look at the correlations between all of the household variables. If there are any that are too highly correlated, then we might want to remove one of the pair of highly correlated variables.

## The following code identifies any variables with a greater than 0.95 absolute magnitude correlation.

## Code to find highly corelated variables

# Create correlation matrix

corr_matrix = heads.corr()

# Select upper triangle of correlation matrix

upper = corr_matrix.where(np.triu(np.ones(corr_matrix.shape), k=1).astype(np.bool))

# Find index of feature columns with correlation greater than 0.95

to_drop = [column for column in upper.columns if any(abs(upper[column]) > 0.95)]

to_drop

['coopele', 'area2', 'tamhog', 'hhsize', 'hogar_total']

These show one out of each pair of correlated variables. To find the other pair, we can subset the corr_matrix.

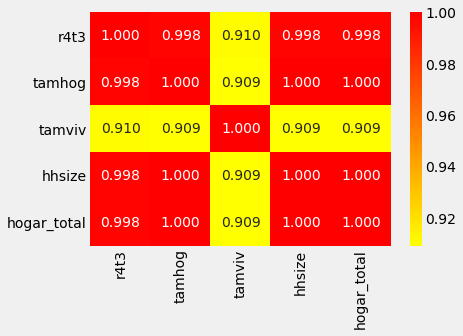

corr_matrix.loc[corr_matrix['tamhog'].abs() > 0.9, corr_matrix['tamhog'].abs() > 0.9]

| r4t3 | tamhog | tamviv | hhsize | hogar_total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r4t3 | 1.000000 | 0.998287 | 0.910457 | 0.998287 | 0.998287 |

| tamhog | 0.998287 | 1.000000 | 0.909155 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| tamviv | 0.910457 | 0.909155 | 1.000000 | 0.909155 | 0.909155 |

| hhsize | 0.998287 | 1.000000 | 0.909155 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| hogar_total | 0.998287 | 1.000000 | 0.909155 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

# Heatmap to see the corelation

sns.heatmap(corr_matrix.loc[corr_matrix['tamhog'].abs() > 0.9, corr_matrix['tamhog'].abs() > 0.9],

annot=True, cmap = plt.cm.autumn_r, fmt='.3f');

There are several variables here having to do with the size of the house:

- r4t3, Total persons in the household

- tamhog, size of the household

- tamviv, number of persons living in the household

- hhsize, household size

- hogar_total, # of total individuals in the household

These variables are all highly correlated with one another. hhsize has a perfect correlation with tamhog and hogar_total. So, we will remove these two variables because the information is redundant. We can also remove r4t3 because it has a near perfect correlation with hhsize. We wil drop tamhog, hogar_total, r4t3

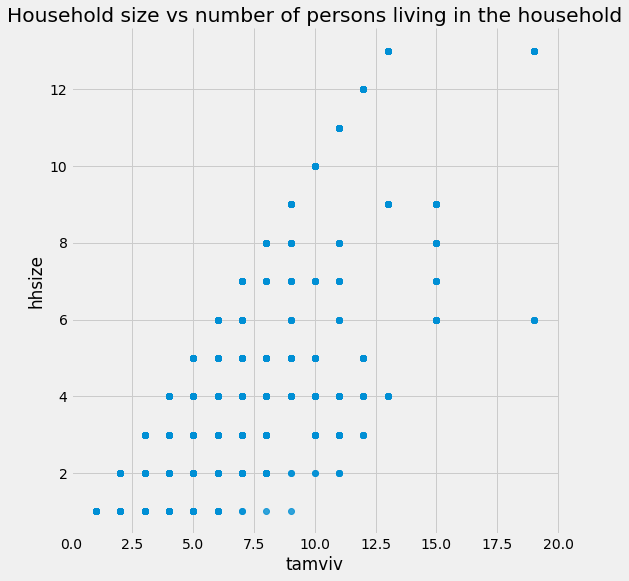

tamviv is not necessarily the same as hhsize because there might be family members that are not living in the household. Let’s visualize this difference in a scatterplot.

heads = heads.drop(columns = ['tamhog', 'hogar_total', 'r4t3'])

# Scatter plot of house size and number of people living in the household

sns.lmplot('tamviv', 'hhsize', data, fit_reg=False, size = 8);

plt.title('Household size vs number of persons living in the household');

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\seaborn\regression.py:546: UserWarning: The `size` paramter has been renamed to `height`; please update your code.

warnings.warn(msg, UserWarning)

We see for a number of cases, there are more people living in the household than there are in the family.

This gives us a good idea for a new feature: the difference between these two measurements!

# Difference between household size and number of people living in that house

heads['hhsize-diff'] = heads['tamviv'] - heads['hhsize']

categorical_plot('hhsize-diff', 'Target', heads)

Even though most households do not have a difference, there are a few that have more people living in the household than are members of the household. Let’s move on to the other redundant variables.

# Let;s look at coopele(electricity from cooperative)

corr_matrix.loc[corr_matrix['coopele'].abs() > 0.9, corr_matrix['coopele'].abs() > 0.9]

| public | coopele | |

|---|---|---|

| public | 1.000000 | -0.967759 |

| coopele | -0.967759 | 1.000000 |

These variables indicate where the electricity in the home is coming from. There are four options, and the families that don’t have one of these two options either have no electricity (noelec) or get it from a private plant (planpri).

Creating Ordinal Variable

We will compress these four variables into one by creating an ordinal variable.

The mapping based on the data decriptions:

- 0: No electricity

- 1: Electricity from cooperative

- 2: Electricity from CNFL, ICA, ESPH/JASEC

- 3: Electricity from private plant

elec = []

# Assign values

for i, row in heads.iterrows():

if row['noelec'] == 1:

elec.append(0)

elif row['coopele'] == 1:

elec.append(1)

elif row['public'] == 1:

elec.append(2)

elif row['planpri'] == 1:

elec.append(3)

else:

elec.append(np.nan)

# Record the new variable and missing flag

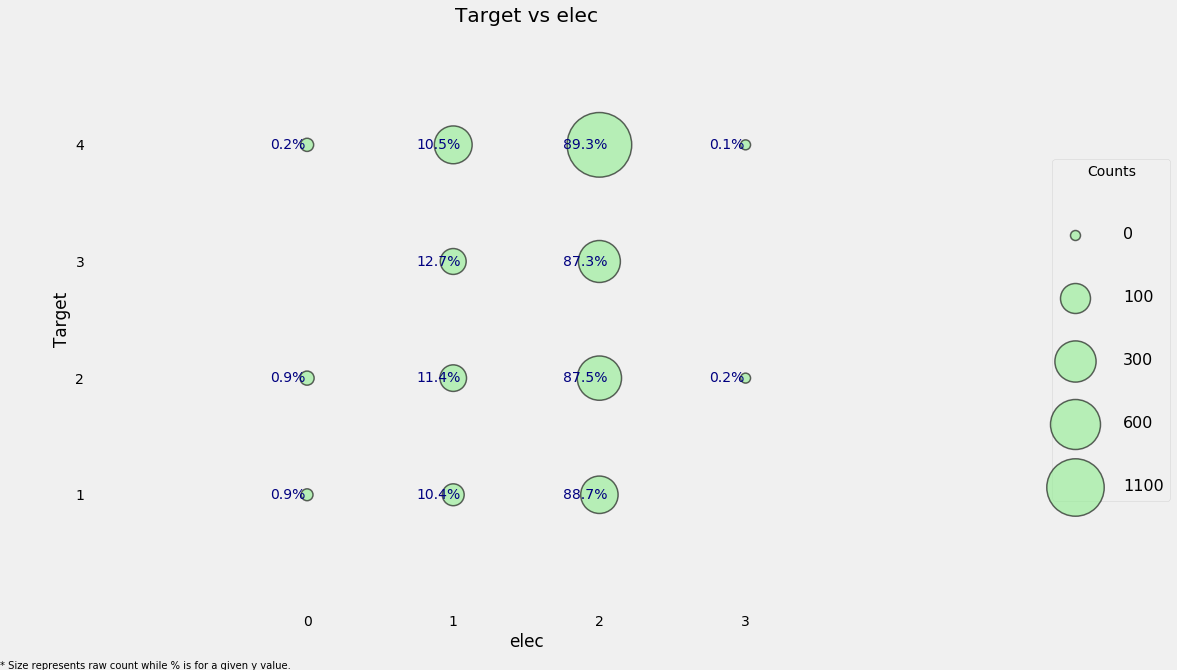

heads['elec'] = elec

heads['elec-missing'] = heads['elec'].isnull()

categorical_plot('elec', 'Target', heads)

We can see that for every value of the Target, the most common source of electricity is from one of the listed providers.

The final redundant column is area2 which means that the house is in a rural zone, but it’s redundant because we have a column indicating if the house is in a urban zone. Therefore, we can drop this column.

heads = heads.drop(columns = 'area2')

heads.groupby('area1')['Target'].value_counts(normalize = True)

area1 Target

0 4.0 0.582249

2.0 0.176331

3.0 0.147929

1.0 0.093491

1 4.0 0.687030

2.0 0.137688

3.0 0.108083

1.0 0.067199

Name: Target, dtype: float64

It seems like households in an urban area (value of 1) are more likely to have lower poverty levels than households in a rural area (value of 0).

Creating Ordinal Variables

So for the walls, roof, and floor of the house, there are three columns each:

- First indicating ‘bad’

- Second ‘regular’

- Third ‘good’.

We could leave the variables as booleans, but to me it makes more sense to turn them into ordinal variables because there is an inherent order: bad < regular < good.

To do this, we can simply find whichever column is non-zero for each household using

np.argmaxand once we have created the ordinal variable, we are able to drop the original variables.

# Wall ordinal variable

heads['walls'] = np.argmax(np.array(heads[['epared1', 'epared2', 'epared3']]),

axis = 1)

# heads = heads.drop(columns = ['epared1', 'epared2', 'epared3'])

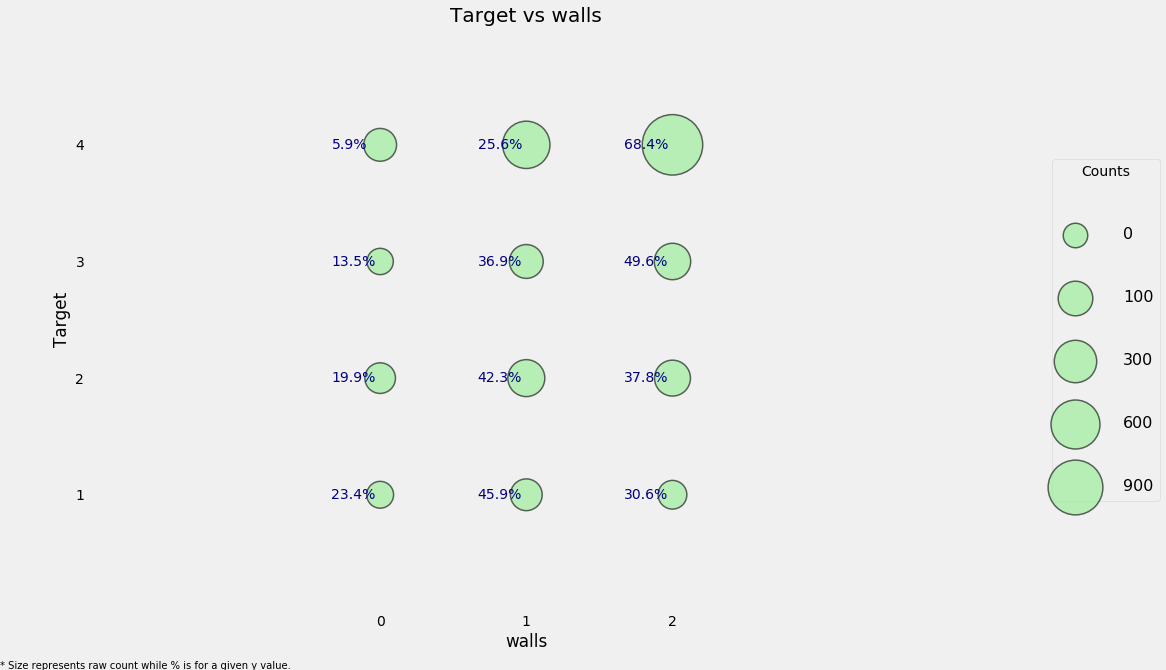

categorical_plot('walls', 'Target', heads)

# Roof ordinal variable

heads['roof'] = np.argmax(np.array(heads[['etecho1', 'etecho2', 'etecho3']]),

axis = 1)

heads = heads.drop(columns = ['etecho1', 'etecho2', 'etecho3'])

# Floor ordinal variable

heads['floor'] = np.argmax(np.array(heads[['eviv1', 'eviv2', 'eviv3']]),

axis = 1)

Feature Construction

We will create a new feature which will add up the previous three features we just created to get an overall measure of the quality of the house’s structure.

# Create new feature (overall quality of the house)

heads['walls+roof+floor'] = heads['walls'] + heads['roof'] + heads['floor']

categorical_plot('walls+roof+floor', 'Target', heads, annotate=False)

This new feature may be useful because it seems like a Target of 4 (the lowest poverty level) tends to have higher values of the ‘house quality’ variable. We can also look at this in a table to get the fine-grained details.

counts = pd.DataFrame(heads.groupby(['walls+roof+floor'])['Target'].value_counts(normalize = True)

).rename(columns = {'Target': 'Normalized Count'}).reset_index()

counts.head()

| walls+roof+floor | Target | Normalized Count | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 4.0 | 0.376404 |

| 1 | 0 | 2.0 | 0.320225 |

| 2 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.162921 |

| 3 | 0 | 3.0 | 0.140449 |

| 4 | 1 | 4.0 | 0.323529 |

The next variable will be a warning about the quality of the house. It will be a negative value, with -1 point each for no toilet, electricity, floor, water service, and ceiling.

# No toilet, no electricity, no floor, no water service, no ceiling

heads['warning'] = 1 * (heads['sanitario1'] +

(heads['elec'] == 0) +

heads['pisonotiene'] +

heads['abastaguano'] +

(heads['cielorazo'] == 0))

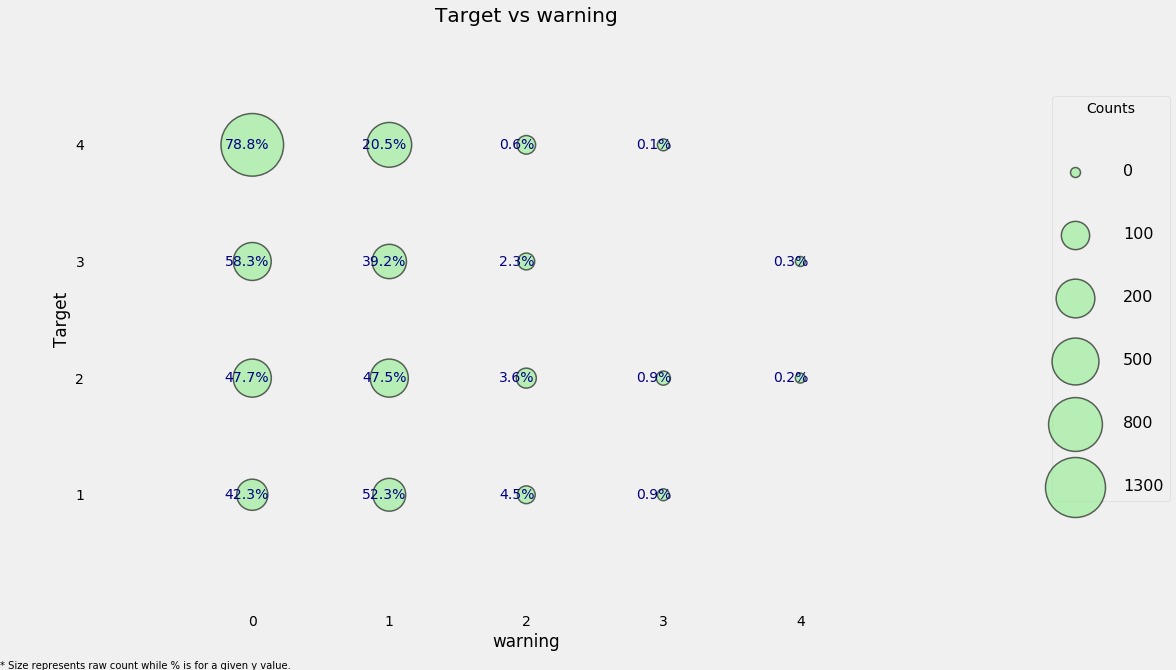

categorical_plot('warning', 'Target', data = heads)

Here we can see a high concentration of households that have no warning signs and have the lowest level of poverty and it looks as if this may be a useful feature.

The final household feature we can make for now is where a family gets a point for having a refrigerator, computer, tablet, or television.

# Owns a refrigerator, computer, tablet, and television

heads['bonus'] = 1 * (heads['refrig'] +

heads['computer'] +

(heads['v18q1'] > 0) +

heads['television'])

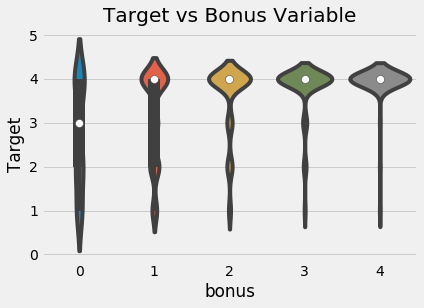

sns.violinplot('bonus', 'Target', data = heads,

figsize = (10, 6));

plt.title('Target vs Bonus Variable');

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

Per Capita Features

We can calculate the number of certain measurements for each person in the household:

tamviv-> Number of person living in the household

heads['phones-per-capita'] = heads['qmobilephone'] / heads['tamviv']

heads['tablets-per-capita'] = heads['v18q1'] / heads['tamviv']

heads['rooms-per-capita'] = heads['rooms'] / heads['tamviv']

heads['rent-per-capita'] = heads['v2a1'] / heads['tamviv']

Exploring Household Variables

Measuring Relationships

There are many ways for measuring relationships between two variables. Here we will examine two of these:

- The Pearson Correlation: from -1 to 1 measuring the linear relationship between two variables

- The Spearman Correlation: from -1 to 1 measuring the monotonic relationship between two variables

The Spearman correlation is 1 if as one variable increases, the other does as well, even if the relationship is not linear. On the other hand, the Pearson correlation can only be one if the increase is exactly linear. These are best illustrated by example.

# The spearmanr correlation

from scipy.stats import spearmanr

The Spearman correlation is often considered to be better for ordinal variables such as the Target or the years of education. Most relationshisp in the real world aren’t linear, and although the Pearson correlation can be an approximation of how related two variables are, it’s inexact and not the best method of comparison. So, first we will calculate the Pearson correlation of every variable with the Target.

# Use only training data

train_heads = heads.loc[heads['Target'].notnull(), :].copy()

pcorrs = pd.DataFrame(train_heads.corr()['Target'].sort_values()).rename(columns = {'Target': 'pcorr'}).reset_index()

pcorrs = pcorrs.rename(columns = {'index': 'feature'})

print('Most negatively correlated variables:')

print(pcorrs.head())

print('\nMost positively correlated variables:')

print(pcorrs.dropna().tail())

Most negatively correlated variables:

feature pcorr

0 warning -0.301791

1 hogar_nin -0.266309

2 r4t1 -0.260917

3 overcrowding -0.234954

4 eviv1 -0.217908

Most positively correlated variables:

feature pcorr

97 phones-per-capita 0.299026

98 floor 0.307605

99 walls+roof+floor 0.332446

100 meaneduc 0.333652

101 Target 1.000000

For the negative correlations, as we increase the variable, the Target decreases indicating the poverty severity increases.

- Therefore, as the warning increases, the poverty level also increases which makes sense because this was meant to show potential bad signs about a house.

- The hogar_nin is the number of children 0 - 19 in the family which also makes sense as younger children can be financial source of stress on a family leading to higher levels of poverty or we can say that the families with lower socioeconomic status have more children in the hopes that one of them will be able to succeed.So there is a real link between family size and poverty

For the positive correlations, a higher value means a higher value of Target indicating the poverty severity decreases.

- The most highly correlated household level variable is meaneduc, the average education level of the adults in the household.This relationship between education and poverty intuitively makes sense as greater levels of education generally correlate with lower levels of poverty.

The general guidelines for correlation values are below, but these will change depending on who you ask (source for these):

- .00-.19 “very weak”

- .20-.39 “weak”

- .40-.59 “moderate”

- .60-.79 “strong”

- .80-1.0 “very strong”

What these correlations show is that there are some weak relationships that hopefully our model will be able to use to learn a mapping from the features to the Target.

Now we can move on to the Spearman correlation.

# Spearman correlation.

feats = []

scorr = []

pvalues = []

# Iterate through each column

for c in heads:

# Only valid for numbers

if heads[c].dtype != 'object':

feats.append(c)

# Calculate spearman correlation

scorr.append(spearmanr(train_heads[c], train_heads['Target']).correlation)

pvalues.append(spearmanr(train_heads[c], train_heads['Target']).pvalue)

scorrs = pd.DataFrame({'feature': feats, 'scorr': scorr, 'pvalue': pvalues}).sort_values('scorr')

The Spearman correlation coefficient calculation also comes with a pvalue indicating the significance level of the relationship. Any pvalue less than 0.05 is genearally regarded as significant, although since we are doing multiple comparisons, we want to divide the p-value by the number of comparisons, a process known as the Bonferroni correction.

print('Most negative Spearman correlations:')

print(scorrs.head())

print('\nMost positive Spearman correlations:')

print(scorrs.dropna().tail())

Most negative Spearman correlations:

feature scorr pvalue

97 warning -0.307326 4.682829e-66

68 dependency -0.281516 2.792620e-55

85 hogar_nin -0.236225 5.567218e-39

80 r4t1 -0.219226 1.112230e-33

49 eviv1 -0.217803 2.952571e-33

Most positive Spearman correlations:

feature scorr pvalue

23 cielorazo 0.300996 2.611808e-63

95 floor 0.309638 4.466091e-67

99 phones-per-capita 0.337377 4.760104e-80

96 walls+roof+floor 0.338791 9.539346e-81

0 Target 1.000000 0.000000e+00

For the most part, the two methods of calculating correlations are in agreement. So let’s look for the values that are furthest apart.

corrs = pcorrs.merge(scorrs, on = 'feature')

corrs['diff'] = corrs['pcorr'] - corrs['scorr']

corrs.sort_values('diff').head()

| feature | pcorr | scorr | pvalue | diff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77 | rooms-per-capita | 0.152185 | 0.223303 | 6.521453e-35 | -0.071119 |

| 85 | v18q1 | 0.197493 | 0.244200 | 1.282664e-41 | -0.046708 |

| 87 | tablets-per-capita | 0.204638 | 0.248642 | 3.951568e-43 | -0.044004 |

| 2 | r4t1 | -0.260917 | -0.219226 | 1.112230e-33 | -0.041691 |

| 97 | phones-per-capita | 0.299026 | 0.337377 | 4.760104e-80 | -0.038351 |

corrs.sort_values('diff').dropna().tail()

| feature | pcorr | scorr | pvalue | diff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57 | techozinc | 0.014357 | 0.003404 | 8.528369e-01 | 0.010954 |

| 49 | hogar_mayor | -0.025173 | -0.041722 | 2.290994e-02 | 0.016549 |

| 88 | edjefe | 0.235687 | 0.214736 | 2.367521e-32 | 0.020951 |

| 66 | edjefa | 0.052310 | 0.005114 | 7.804715e-01 | 0.047197 |

| 17 | dependency | -0.126465 | -0.281516 | 2.792620e-55 | 0.155051 |

The largest discrepancy in the correlations is dependency. We can make a scatterplot of the Target versus the dependency to visualize the relationship. We’ll add a little jitter to the plot because these are both discrete variables.

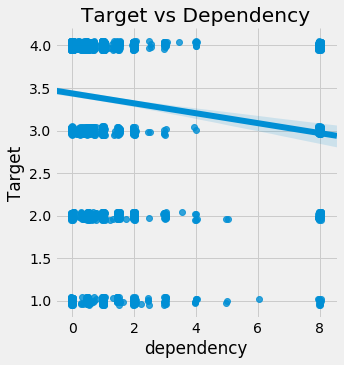

sns.lmplot('dependency', 'Target', fit_reg = True, data = train_heads, x_jitter=0.05, y_jitter=0.05);

plt.title('Target vs Dependency');

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

It’s hard to see the relationship, but it’s slightly negative: as the dependency increases, the value of the Target decreases. This actually makes sense as the dependency is the number of dependent individuals divided by the number of non-dependents. As we increase this value, the poverty severty tends to increase: having more dependent family members (who usually are non-working) leads to higher levels of poverty because they must be supported by the non-dependent family members.

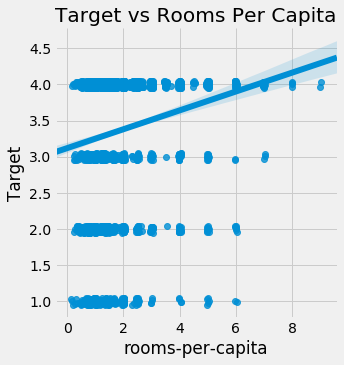

sns.lmplot('rooms-per-capita', 'Target', fit_reg = True, data = train_heads, x_jitter=0.05, y_jitter=0.05);

plt.title('Target vs Rooms Per Capita');

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

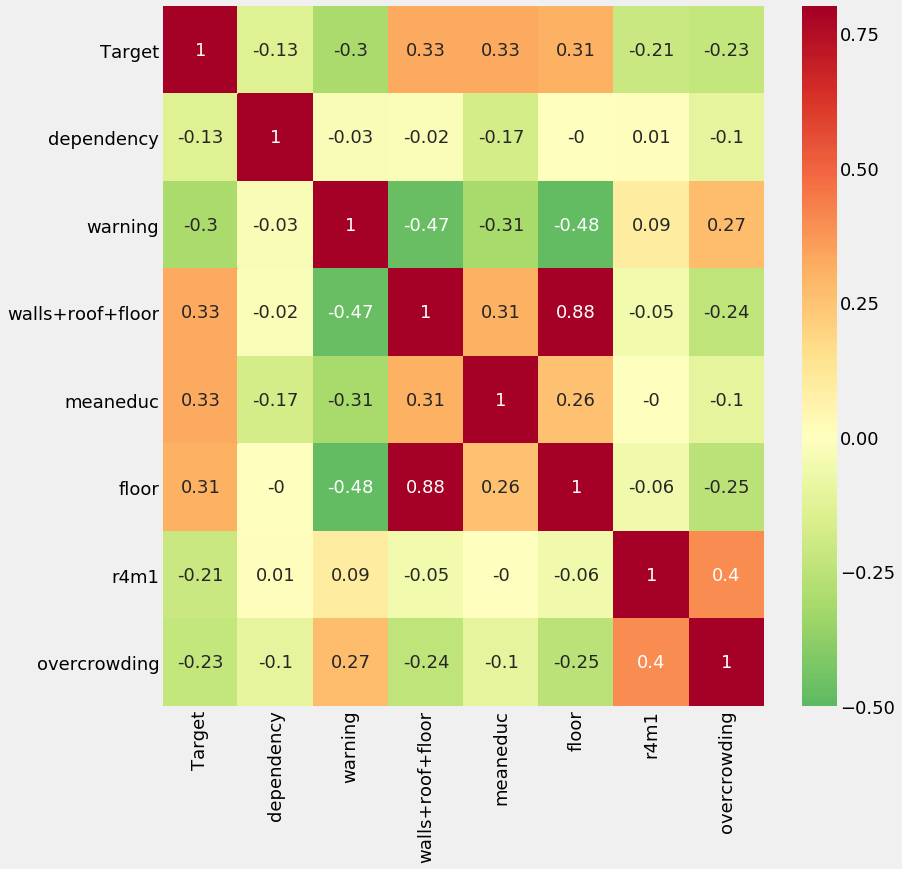

Correlation Heatmap

For the heatmap, we will pick 7 variables and show the correlations between themselves and with the target.

variables = ['Target', 'dependency', 'warning', 'walls+roof+floor', 'meaneduc',

'floor', 'r4m1', 'overcrowding']

# Calculate the correlations

corr_mat = train_heads[variables].corr().round(2)

# Draw a correlation heatmap

plt.rcParams['font.size'] = 18

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 12))

sns.heatmap(corr_mat, vmin = -0.5, vmax = 0.8, center = 0,

cmap = plt.cm.RdYlGn_r, annot = True);

This plot shows us that there are a number of variables that have a weak correlation with the Target. There are also high correlations between some variables (such as floor and walls+roof+floor) which could pose an issue because of collinearity.

household_feats = list(heads.columns)

Individual Level Variables

There are two types of individual level variables: Boolean (1 or 0 for True or False) and ordinal (discrete values with a meaningful ordering)

ind = data[id_ + ind_bool + ind_ordered]

ind.shape

(33413, 40)

Redundant Individual Variables

We can do the same process we did with the household level variables to identify any redundant individual variables. We’ll focus on any variables that have an absolute magnitude of the correlation coefficient greater than 0.95.

# Create correlation matrix

corr_matrix = ind.corr()

# Select upper triangle of correlation matrix

upper = corr_matrix.where(np.triu(np.ones(corr_matrix.shape), k=1).astype(np.bool))

# Find index of feature columns with correlation greater than 0.95

to_drop = [column for column in upper.columns if any(abs(upper[column]) > 0.95)]

to_drop

['female']

This is simply the opposite of male! We can remove the male flag.

ind = ind.drop(columns = 'male')

Creating Ordinal Variables

Much as we did with the household level data, we can map existing columns to an ordinal variable. Here we will focus on the

- instlevel_: variables which indicate the amount of education an individual has from

- instlevel1: no level of education to

- instlevel9: postgraduate education.

To create the ordinal variable, for each individual, we will simply find which column is non-zero. The education has an inherent ordering (higher is better) so this conversion to an ordinal variable makes sense in the problem context.

ind[[c for c in ind if c.startswith('instl')]].head()

| instlevel1 | instlevel2 | instlevel3 | instlevel4 | instlevel5 | instlevel6 | instlevel7 | instlevel8 | instlevel9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

ind['inst'] = np.argmax(np.array(ind[[c for c in ind if c.startswith('instl')]]), axis = 1)

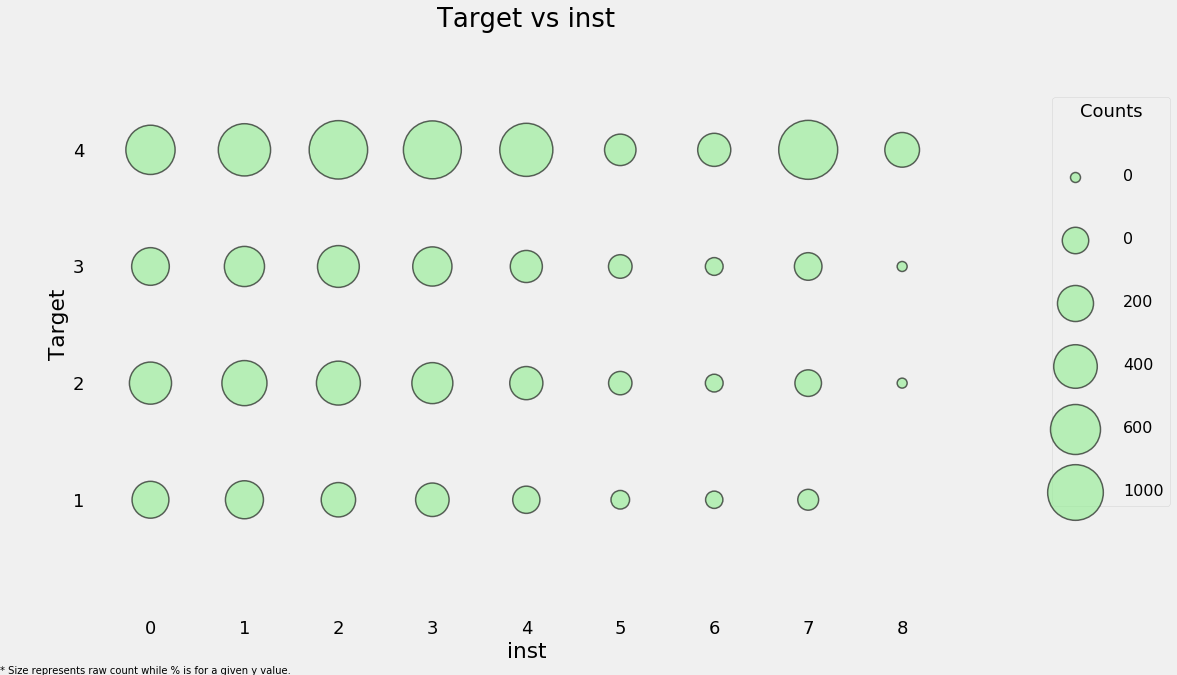

categorical_plot('inst', 'Target', ind, annotate = False);

Higher levels of education seem to correspond to less extreme levels of poverty. We do need to keep in mind this is on an individual level though and we eventually will have to aggregate this data at the household level.

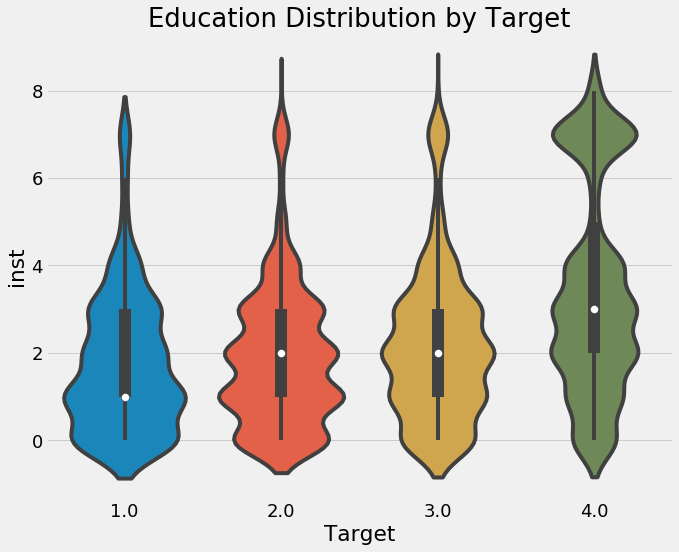

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 8))

sns.violinplot(x = 'Target', y = 'inst', data = ind);

plt.title('Education Distribution by Target');

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

ind.shape

(33413, 40)

Feature Construction

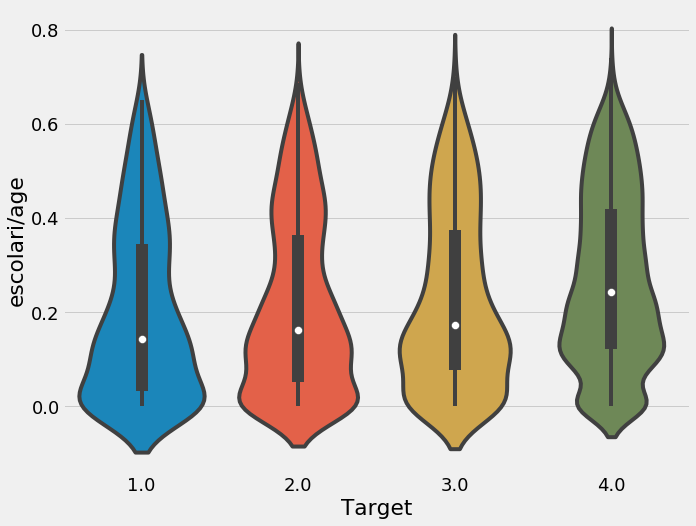

We will make a few features using the existing data by dividing the years of schooling by the age. Which is a good way to see the education and age.

ind['escolari/age'] = ind['escolari'] / ind['age']

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 8))

sns.violinplot('Target', 'escolari/age', data = ind);

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

We can also take our new variable, inst, and divide this by the age. The final variable we’ll name tech: this represents the combination of tablet and mobile phones.

ind['inst/age'] = ind['inst'] / ind['age']

ind['tech'] = ind['v18q'] + ind['mobilephone']

ind['tech'].describe()

count 33413.000000

mean 1.214886

std 0.462567

min 0.000000

25% 1.000000

50% 1.000000

75% 1.000000

max 2.000000

Name: tech, dtype: float64

Feature Engineering through Aggregations

In order to incorporate the individual data into the household data, we need to aggregate it for each household.

# Define custom function

range_ = lambda x: x.max() - x.min()

range_.__name__ = 'range_'

# Group and aggregate

ind_agg = ind.drop(columns = 'Target').groupby('idhogar').agg(['min', 'max', 'sum', 'count', 'std', range_])

So now we have 180 features instead of 30 features. W will rename the columns to make it easier to keep track.

# Rename the columns

new_col = []

for c in ind_agg.columns.levels[0]:

for stat in ind_agg.columns.levels[1]:

new_col.append(f'{c}-{stat}')

ind_agg.columns = new_col

ind_agg.iloc[:, [0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9]].head()

| v18q-min | v18q-max | v18q-sum | v18q-count | dis-min | dis-max | dis-sum | dis-count | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| idhogar | ||||||||

| 000a08204 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 000bce7c4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 001845fb0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 001ff74ca | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 003123ec2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

Feature Selection

As a first round of feature selection, we can remove one out of every pair of variables with a correlation greater than 0.95.

# Create correlation matrix

corr_matrix = ind_agg.corr()

# Select upper triangle of correlation matrix

upper = corr_matrix.where(np.triu(np.ones(corr_matrix.shape), k=1).astype(np.bool))

# Find index of feature columns with correlation greater than 0.95

to_drop = [column for column in upper.columns if any(abs(upper[column]) > 0.95)]

print(f'There are {len(to_drop)} correlated columns to remove.')

There are 111 correlated columns to remove.

We’ll drop the columns and then merge with the heads data to create a final dataframe.

ind_agg = ind_agg.drop(columns = to_drop)

ind_feats = list(ind_agg.columns)

# Merge on the household id

final = heads.merge(ind_agg, on = 'idhogar', how = 'left')

print('Final features shape: ', final.shape)

Final features shape: (10307, 228)

Final Data Exploration

We’ll do a little bit of exploration.

corrs = final.corr()['Target']

corrs.sort_values().head()

warning -0.301791

instlevel2-sum -0.297868

instlevel1-sum -0.271204

hogar_nin -0.266309

r4t1 -0.260917

Name: Target, dtype: float64

corrs.sort_values().dropna().tail()

walls+roof+floor 0.332446

meaneduc 0.333652

inst-max 0.368229

escolari-max 0.373091

Target 1.000000

Name: Target, dtype: float64

We can see some of the variables that we made are highly correlated with the Target. Whether these variables are actually useful will be determined in the modeling stage.

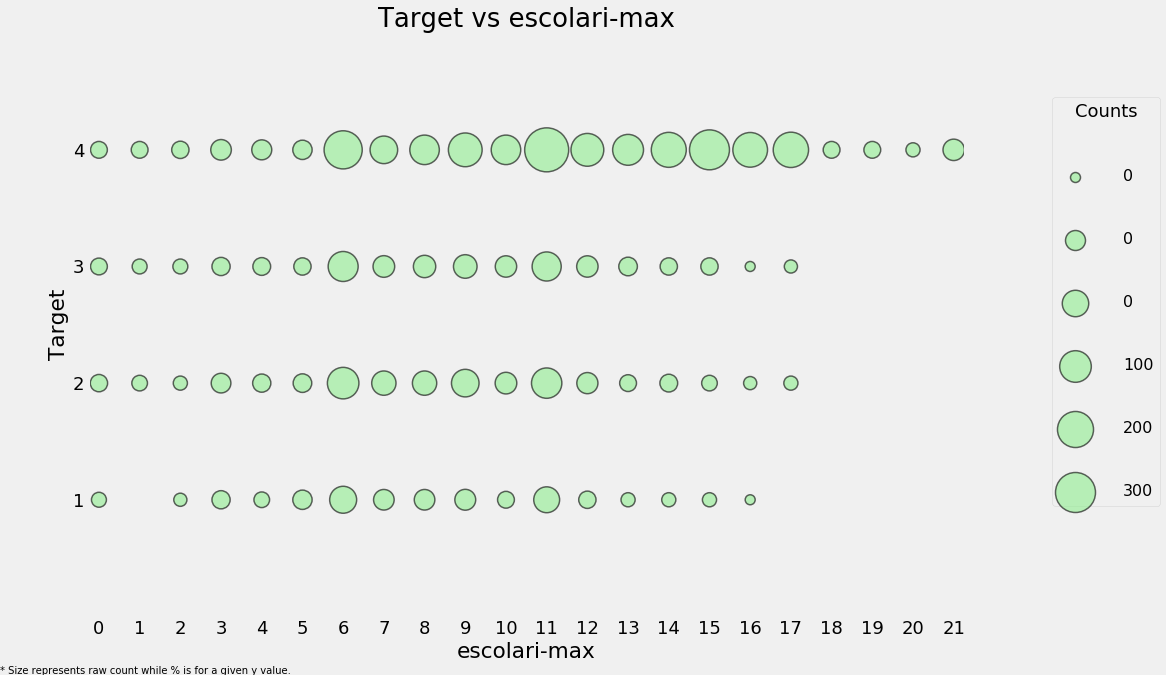

categorical_plot('escolari-max', 'Target', final, annotate=False);

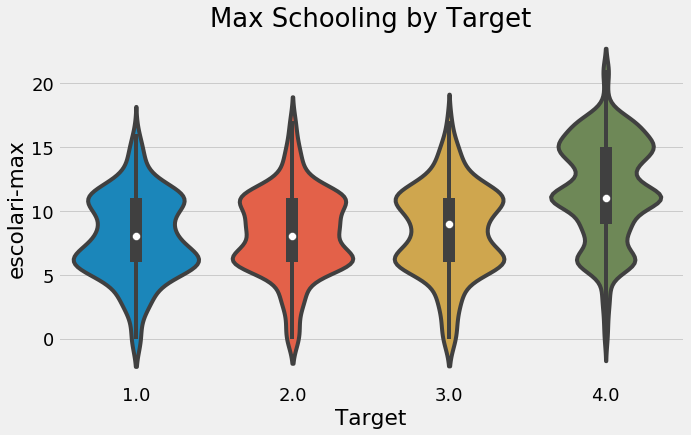

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 6))

sns.violinplot(x = 'Target', y = 'escolari-max', data = final);

plt.title('Max Schooling by Target');

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

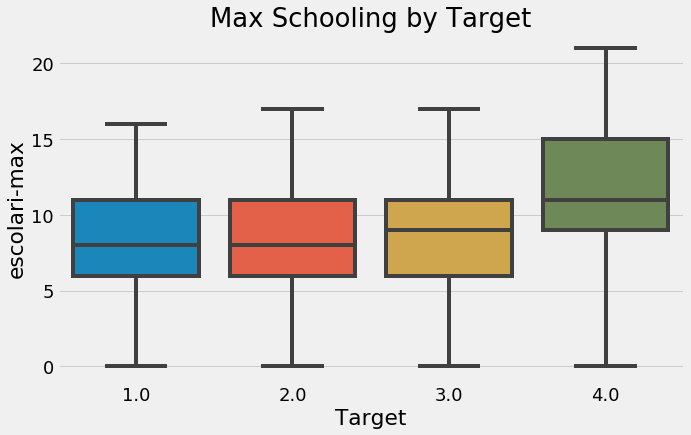

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 6))

sns.boxplot(x = 'Target', y = 'escolari-max', data = final);

plt.title('Max Schooling by Target');

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 6))

sns.boxplot(x = 'Target', y = 'meaneduc', data = final);

plt.xticks([0, 1, 2, 3], poverty_mapping.values())

plt.title('Average Schooling by Target');

plt.figure(figsize = (10, 6))

sns.boxplot(x = 'Target', y = 'overcrowding', data = final);

plt.xticks([0, 1, 2, 3], poverty_mapping.values())

plt.title('Overcrowding by Target');

One other feature that might be useful is the gender of the head of household. Since we aggregated the data, we’ll have to go back to the individual level data and find the gender for the head of household.

head_gender = ind.loc[ind['parentesco1'] == 1, ['idhogar', 'female']]

final = final.merge(head_gender, on = 'idhogar', how = 'left').rename(columns =

{'female': 'female-head'})

final.groupby('female-head')['Target'].value_counts(normalize=True)

female-head Target

0 4.0 0.682873

2.0 0.136464

3.0 0.123204

1.0 0.057459

1 4.0 0.617369

2.0 0.167670

3.0 0.113500

1.0 0.101462

Name: Target, dtype: float64

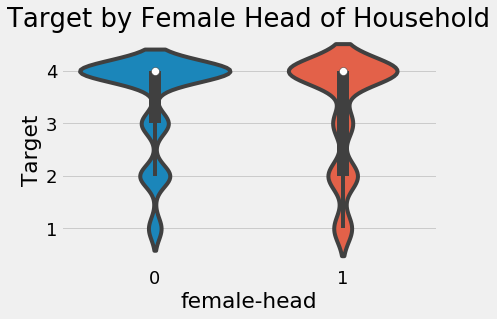

It looks like households where the head is female are slightly more likely to have a severe level of poverty.

sns.violinplot(x = 'female-head', y = 'Target', data = final);

plt.title('Target by Female Head of Household');

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

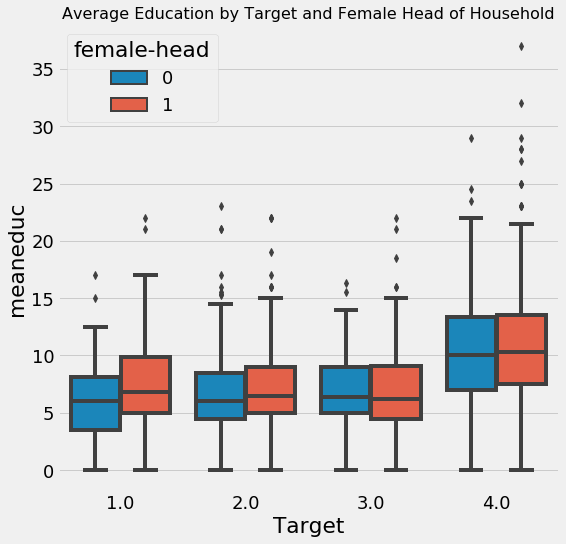

We will also look at the difference in average education by whether or not the family has a female head of household.

plt.figure(figsize = (8, 8))

sns.boxplot(x = 'Target', y = 'meaneduc', hue = 'female-head', data = final);

plt.title('Average Education by Target and Female Head of Household', size = 16);

It looks like at every value of the Target, households with female heads have higher levels of education. Yet, we saw that overall, households with female heads are more likely to have severe poverty.

final.groupby('female-head')['meaneduc'].agg(['mean', 'count'])

| mean | count | |

|---|---|---|

| female-head | ||

| 0 | 8.968025 | 6384 |

| 1 | 9.237013 | 3903 |

Overall, the average education of households with female heads is slightly higher than those with male heads. I’m not too sure what to make of this, but it seems right to me.

Machine Learning Modeling

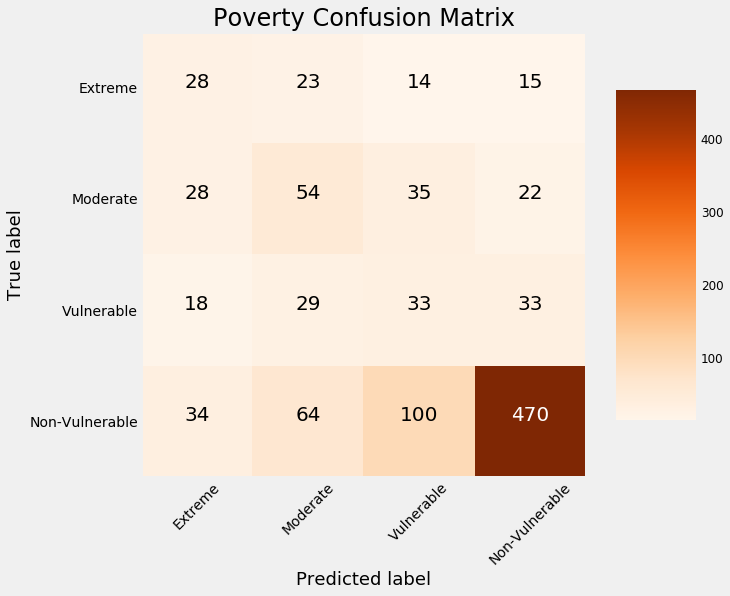

To assess our model, we’ll use 10-fold cross validation on the training data. This will essentially train and test the model 10 times using different splits of the training data. 10-fold cross validation is an effective method for estimating the performance of a model on the test set. We want to look at the average performance in cross validation as well as the standard deviation to see how much scores change between the folds. We use the F1 Macro measure to evaluate performance.

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

from sklearn.metrics import f1_score, make_scorer

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

from sklearn.preprocessing import Imputer

from sklearn.preprocessing import MinMaxScaler

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

# Custom scorer for cross validation

scorer = make_scorer(f1_score, greater_is_better=True, average = 'macro')

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\sklearn\ensemble\weight_boosting.py:29: DeprecationWarning: numpy.core.umath_tests is an internal NumPy module and should not be imported. It will be removed in a future NumPy release.

from numpy.core.umath_tests import inner1d

# Labels for training

train_labels = np.array(list(final[final['Target'].notnull()]['Target'].astype(np.uint8)))

# Extract the training data

train_set = final[final['Target'].notnull()].drop(columns = ['Id', 'idhogar', 'Target'])

test_set = final[final['Target'].isnull()].drop(columns = ['Id', 'idhogar', 'Target'])

# Submission base which is used for making submissions to the competition

submission_base = test[['Id', 'idhogar']].copy()

We will be comparing different models, So we want to scale the features (limit the range of each column to between 0 and 1). For many ensemble models this is not necessary, but when we use models that depend on a distance metric, such as KNearest Neighbors or the Support Vector Machine, feature scaling is an absolute necessity. When comparing different models, it’s always safest to scale the features. We also impute the missing values with the median of the feature.

For imputing missing values and scaling the features in one step, we can make a pipeline. This will be fit on the training data and used to transform the training and testing data.

features = list(train_set.columns)

pipeline = Pipeline([('imputer', Imputer(strategy = 'median')),

('scaler', MinMaxScaler())])

# Fit and transform training data

train_set = pipeline.fit_transform(train_set)

test_set = pipeline.transform(test_set)

model = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=100, random_state=10,

n_jobs = -1)

# 10 fold cross validation

cv_score = cross_val_score(model, train_set, train_labels, cv = 10, scoring = scorer)

print(f'10 Fold Cross Validation F1 Score = {round(cv_score.mean(), 4)} with std = {round(cv_score.std(), 4)}')

10 Fold Cross Validation F1 Score = 0.3425 with std = 0.0322

The data has no missing values and is scaled between zero and one. This means it can be directly used in any Scikit-Learn model.

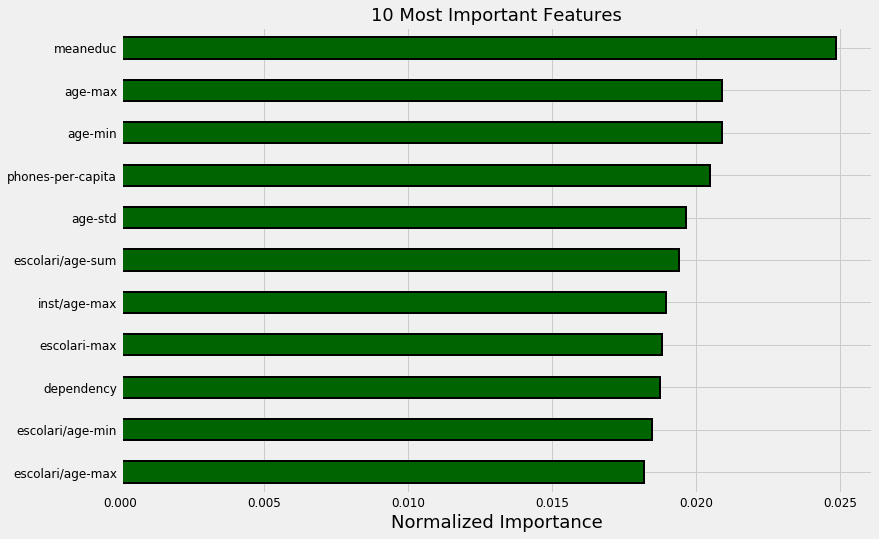

Feature Importances

With a tree-based model, we can look at the feature importances which show a relative ranking of the usefulness of features in the model. These represent the sum of the reduction in impurity at nodes that used the variable for splitting, but we don’t have to pay much attention to the absolute value. Instead we’ll focus on relative scores.

model.fit(train_set, train_labels)

# Feature importances into a dataframe

feature_importances = pd.DataFrame({'feature': features, 'importance': model.feature_importances_})

feature_importances.head()

| feature | importance | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | hacdor | 0.000643 |

| 1 | hacapo | 0.000283 |

| 2 | v14a | 0.000460 |

| 3 | refrig | 0.001798 |

| 4 | paredblolad | 0.006024 |

# Import Function to plot the feature importances

from costarican.featurePlot import feature_importances_plot

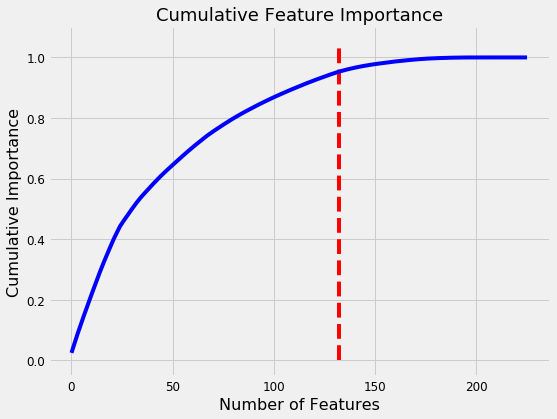

norm_fi = feature_importances_plot(feature_importances, threshold=0.95)

132 features required for 95% of cumulative importance.

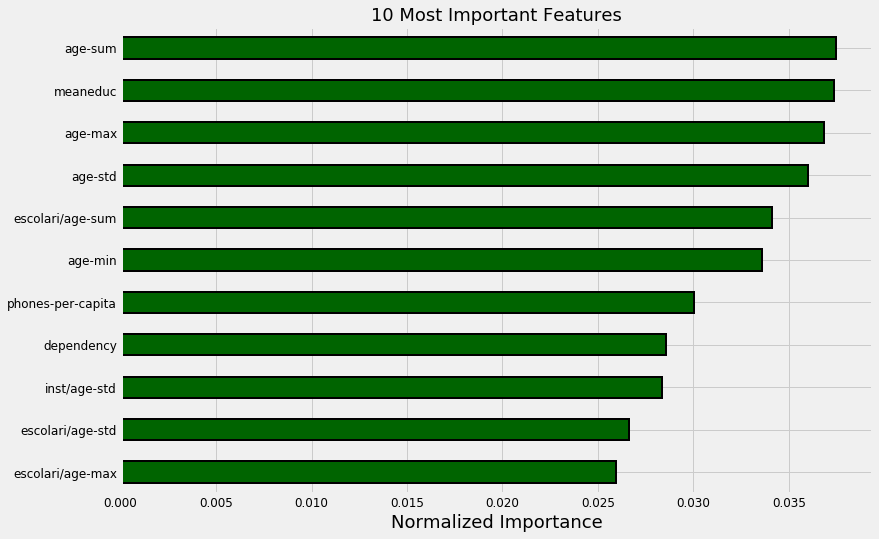

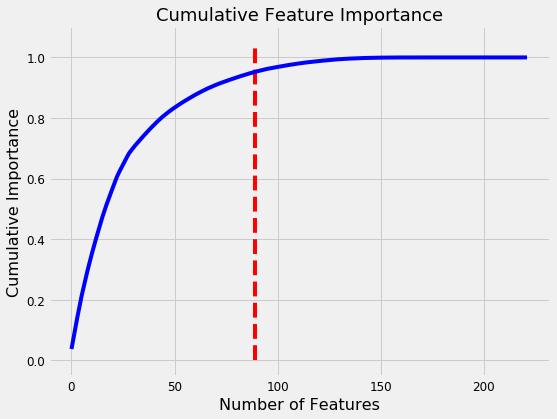

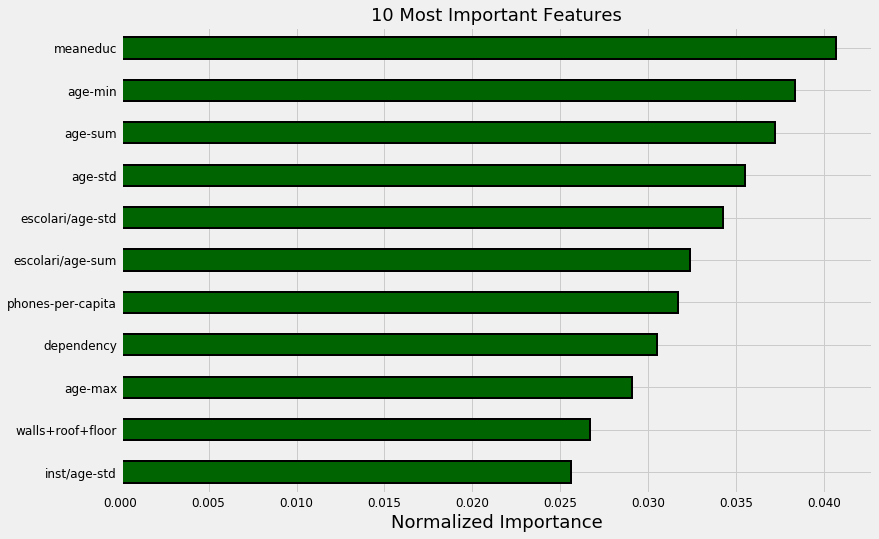

The most important variable is the average amount of education in the household, followed by the maximum education of anyone in the household. I have a suspicion these variables are highly correlated (collinear) which means we may want to remove one of them from the data. The other most important features are a combination of variables we created and variables that were already present in the data.

It’s interesting that we only need 132 of the ~180 features to account for 95% of the importance. This tells us that we may be able to remove some of the features. However, feature importances don’t tell us which direction of the feature is important (for example, we can’t use these to tell whether more or less education leads to more severe poverty) they only tell us which features the model considered relevant.

# Import function to plot the distribution of variables

from costarican.distributionPlot import kde_target

kde_target(final, 'meaneduc')

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

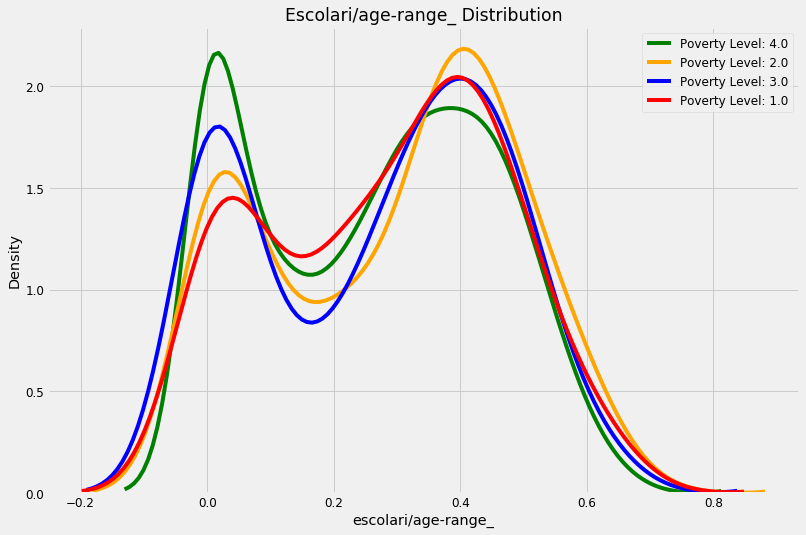

kde_target(final, 'escolari/age-range_')

C:\Anaconda\lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\stats.py:1713: FutureWarning: Using a non-tuple sequence for multidimensional indexing is deprecated; use `arr[tuple(seq)]` instead of `arr[seq]`. In the future this will be interpreted as an array index, `arr[np.array(seq)]`, which will result either in an error or a different result.

return np.add.reduce(sorted[indexer] * weights, axis=axis) / sumval

Model Selection

In addition to the Random Forest Classifier, we’ll try eight other Scikit-Learn models. Luckily, this dataset is relatively small and we can rapidly iterate through the models. We will make a dataframe to hold the results and the function will add a row to the dataframe for each model.

# Model imports

from sklearn.svm import LinearSVC

from sklearn.naive_bayes import GaussianNB

from sklearn.neural_network import MLPClassifier

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegressionCV, RidgeClassifierCV

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import LinearDiscriminantAnalysis

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

import warnings

from sklearn.exceptions import ConvergenceWarning

# Filter out warnings from models

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore', category = ConvergenceWarning)

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore', category = DeprecationWarning)

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore', category = UserWarning)

# Dataframe to hold results

model_results = pd.DataFrame(columns = ['model', 'cv_mean', 'cv_std'])

def cv_model(train, train_labels, model, name, model_results=None):

"""Perform 10 fold cross validation of a model"""

cv_scores = cross_val_score(model, train, train_labels, cv = 10, scoring=scorer, n_jobs = -1)

print(f'10 Fold CV Score: {round(cv_scores.mean(), 5)} with std: {round(cv_scores.std(), 5)}')

if model_results is not None:

model_results = model_results.append(pd.DataFrame({'model': name,

'cv_mean': cv_scores.mean(),

'cv_std': cv_scores.std()},

index = [0]),

ignore_index = True)

return model_results

model_results = cv_model(train_set, train_labels, LinearSVC(),

'LSVC', model_results)

10 Fold CV Score: 0.28346 with std: 0.04484

That’s one model to cross off the list (although we didn’t perform hyperparameter tuning so the actual performance could possibly be improved).

model_results = cv_model(train_set, train_labels,

GaussianNB(), 'GNB', model_results)

10 Fold CV Score: 0.17935 with std: 0.03867

That performance is very poor. I don’t think we need to revisit the Gaussian Naive Bayes method (although there are problems on which it can outperform the Gradient Boosting Machine).

model_results = cv_model(train_set, train_labels,

LinearDiscriminantAnalysis(),

'LDA', model_results)

10 Fold CV Score: 0.32217 with std: 0.05984

If you run LinearDiscriminantAnalysis without filtering out the UserWarnings, you get many messages saying “Variables are collinear.” This might give us a hint that we want to remove some collinear features! We might want to try this model again after removing the collinear variables because the score is comparable to the random forest.

model_results = cv_model(train_set, train_labels,

RidgeClassifierCV(), 'RIDGE', model_results)

10 Fold CV Score: 0.27896 with std: 0.03675

The linear model (with ridge regularization) does surprisingly well. This might indicate that a simple model can go a long way in this problem (although we’ll probably end up using a more powerful method).

for n in [5, 10, 20]:

print(f'\nKNN with {n} neighbors\n')

model_results = cv_model(train_set, train_labels,

KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors = n),

f'knn-{n}', model_results)

KNN with 5 neighbors

10 Fold CV Score: 0.35078 with std: 0.03829

KNN with 10 neighbors

10 Fold CV Score: 0.32153 with std: 0.03028

KNN with 20 neighbors

10 Fold CV Score: 0.31039 with std: 0.04974

As one more attempt, we’ll consider the ExtraTreesClassifier, a variant on the random forest using ensembles of decision trees as well.

from sklearn.ensemble import ExtraTreesClassifier

model_results = cv_model(train_set, train_labels,

ExtraTreesClassifier(n_estimators = 100, random_state = 10),

'EXT', model_results)

10 Fold CV Score: 0.32215 with std: 0.04671

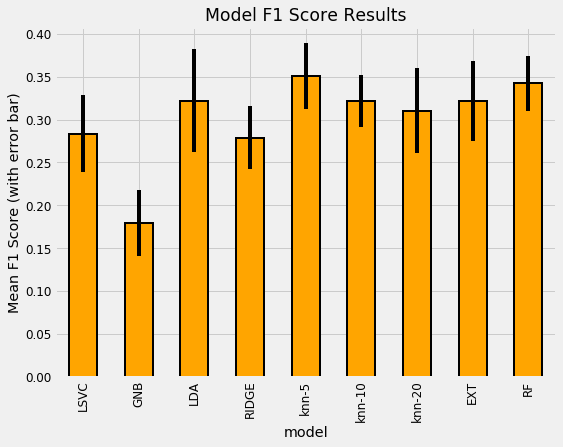

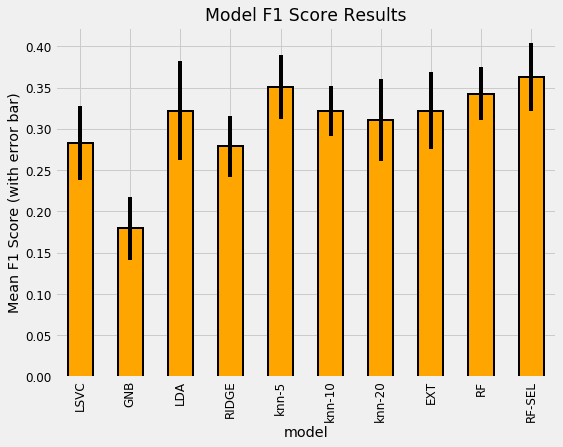

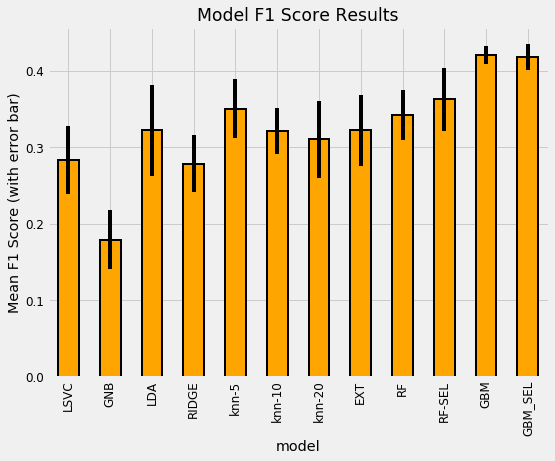

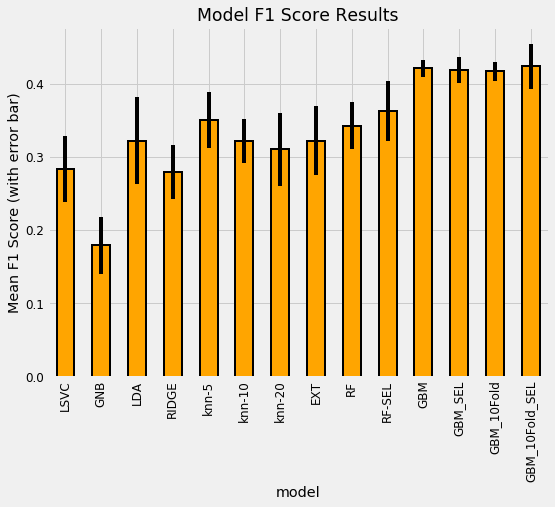

Comparing Model Performance

With the modeling results in a dataframe, we can plot them to see which model does the best.

model_results = cv_model(train_set, train_labels,

RandomForestClassifier(100, random_state=10),

'RF', model_results)

10 Fold CV Score: 0.34245 with std: 0.03221

model_results.set_index('model', inplace = True)

model_results['cv_mean'].plot.bar(color = 'orange', figsize = (8, 6),

yerr = list(model_results['cv_std']),

edgecolor = 'k', linewidth = 2)

plt.title('Model F1 Score Results');

plt.ylabel('Mean F1 Score (with error bar)');

model_results.reset_index(inplace = True)

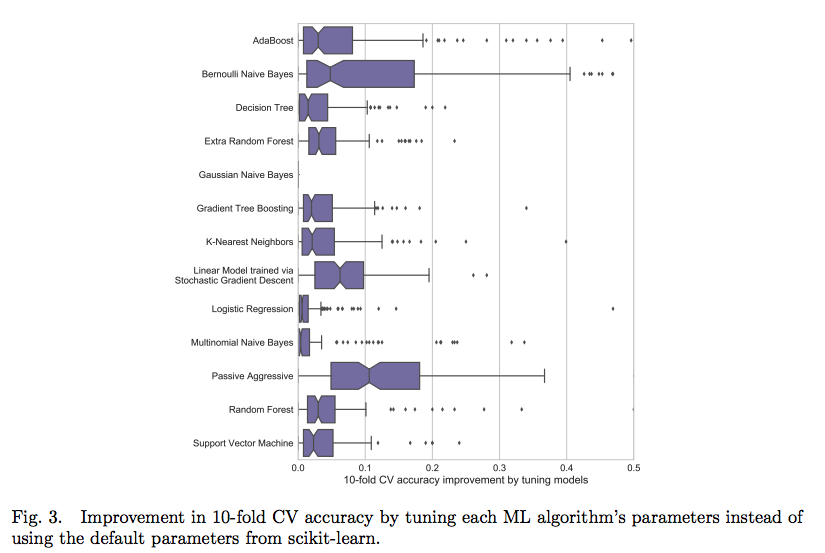

The most well performed model seems to be the Random Forest because it does best right out of the box. While we didn’t tune any of the hyperparameters so the comparison between models is not perfect, these results reflect those of many other Kaggle competitiors finding that tree-based ensemble methods (including the Gradient Boosting Machine) perform very well on structured datasets. Hyperparameter performance does improve the performance of machine learning models, but we don’t have time to try all possible combinations of settings for all models. The graph below (from the paper by Randal Olson) shows the effect of hyperparameter tuning versus the default values in Scikit-Learn.

In most cases the accuracy gain is less than 10% so the worst model is probably not suddenly going to become the best model through tuning.

For now we’ll say the random forest does the best. Later we’ll look at using the Gradient Boosting Machine, although not implemented in Scikit-Learn. Instead we’ll be using the more powerful LightGBM version. Now, let’s turn to making a submission using the random forest.

Performance

In order to see the performance of our model, we need the test data. Fortunately, we have the test data formatted in exactly the same manner as the train data.

The format of a testing the output is shown below. Although we are making predictions for each household, we actually need one row per individual (identified by the Id) but only the prediction for the head of household is scored.

Id, Target

- ID_2f6873615, 1

- ID_1c78846d2, 2

- ID_e5442cf6a, 3

- ID_a8db26a79, 4

- ID_a62966799, 4

The submission_base will have all the individuals in the test set since we have to have a “prediction” for each individual while the test_ids will only contain the idhogar from the heads of households. When predicting, we only predict for each household and then we merge the predictions dataframe with all of the individuals on the household id (idhogar). This will set the Target to the same value for everyone in a household. For the test households without a head of household, we can just set these predictions to 4 since they will not be scored.

test_ids = list(final.loc[final['Target'].isnull(), 'idhogar'])

def submit(model, train, train_labels, test, test_ids):

"""Train and test a model on the dataset"""

# Train on the data

model.fit(train, train_labels)

predictions = model.predict(test)

predictions = pd.DataFrame({'idhogar': test_ids,

'Target': predictions})

# Make a submission dataframe

submission = submission_base.merge(predictions,

on = 'idhogar',

how = 'left').drop(columns = ['idhogar'])

# Fill in households missing a head

submission['Target'] = submission['Target'].fillna(4).astype(np.int8)

return submission

Let’s make a prediction n with the Random Forest.

rf_submission = submit(RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators = 100,

random_state=10, n_jobs = -1),

train_set, train_labels, test_set, test_ids)

rf_submission.to_csv('rf_submission.csv', index = False)

These predictions score 0.360 when submitted to the competition.

Feature Selection

We’ll remove any columns with greater than 0.95 correlation and then we’ll apply recursive feature elimination with the Scikit-Learn library.

First up are the correlations. 0.95 is an arbitrary threshold.

train_set = pd.DataFrame(train_set, columns = features)

# Create correlation matrix

corr_matrix = train_set.corr()

# Select upper triangle of correlation matrix

upper = corr_matrix.where(np.triu(np.ones(corr_matrix.shape), k=1).astype(np.bool))

# Find index of feature columns with correlation greater than 0.95

to_drop = [column for column in upper.columns if any(abs(upper[column]) > 0.95)]

to_drop

['coopele', 'elec', 'v18q-count', 'female-sum']

train_set = train_set.drop(columns = to_drop)

train_set.shape

(2973, 222)

test_set = pd.DataFrame(test_set, columns = features)

train_set, test_set = train_set.align(test_set, axis = 1, join = 'inner')

features = list(train_set.columns)

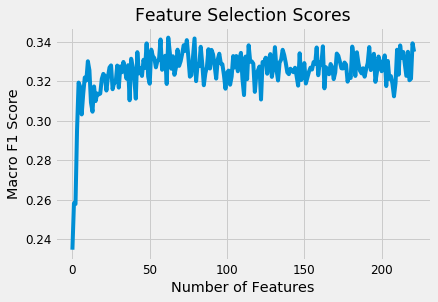

Recursive Feature Elimination with Random Forest

The RFECV in Sklearn stands for Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross Validation. The selector operates using a model with feature importances in an iterative manner. At each iteration, it removes either a fraction of features or a set number of features. The iterations continue until the cross validation score no longer improves.

To create the selector object, we pass in the the model, the number of features to remove at each iteration, the cross validation folds, our custom scorer, and any other parameters to guide the selection.

from sklearn.feature_selection import RFECV

# Create a model for feature selection

estimator = RandomForestClassifier(random_state = 10, n_estimators = 100, n_jobs = -1)

# Create the object

selector = RFECV(estimator, step = 1, cv = 3, scoring= scorer, n_jobs = -1)

Then we fit the selector on the training data as with any other sklearn model. This will continue the feature selection until the cross validation scores no longer improve.

selector.fit(train_set, train_labels)

RFECV(cv=3,

estimator=RandomForestClassifier(bootstrap=True, class_weight=None, criterion='gini',

max_depth=None, max_features='auto', max_leaf_nodes=None,

min_impurity_decrease=0.0, min_impurity_split=None,

min_samples_leaf=1, min_samples_split=2,

min_weight_fraction_leaf=0.0, n_estimators=100, n_jobs=-1,

oob_score=False, random_state=10, verbose=0, warm_start=False),

n_jobs=-1, scoring=make_scorer(f1_score, average=macro), step=1,

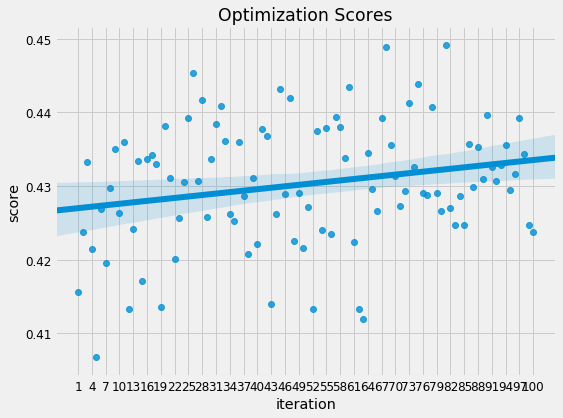

verbose=0)